DAY ONE: Assange Timeline Exposes US Motives

February 20, 2024

Julian Assange’s lawyers on Tuesday argued before the High Court about why the imprisoned publisher must be allowed to appeal against his extradition order, reports Joe Lauria.

By Joe Lauria, in London, Consortium News

On Day One of Julian Assange’s attempt to appeal Britain’s order to extradite him to the United States, his lawyers laid out a timeline that exposed U.S. motives to destroy the journalist who revealed their high-level state crimes.

Before two High Court judges in the cramped, wood-paneled Courtroom 5 at the Royal Courts of Justice, Assange’s lawyers argued on Tuesday that two judges had seriously erred in the case on a number of grounds necessitating an appeal of the home secretary’s decision to extradite Assange to the United States.

High to the left of the court, next to oak shelves with neat rows of law books, was an empty iron cage. The court said it had invited Assange to either attend in person or via video link from Belmarsh Prison, where he has been locked up on remand for nearly five years. But Assange said he was too ill take part in any capacity, his lawyers confirmed.

Vanessa Baraitser, the district judge who presided over Assange’s 2020 extradition hearing, and Jonathan Swift, a High Court judge, came in for heavy criticism from Assange’s lawyers. Baraitser in January 2021 ordered Assange released on health grounds.

But she refused him bail while the U.S. appealed. On the basis of assurances that it would not mistreat Assange in the United States, the High Court reversed Baraitser’s decision. The U.K. Supreme Court then refused to take Assange’s challenge of the legality of these assurance and the home secretary signed the extradition order.

Assange’s last avenue of appeal is of the home secretary’s order as well as Baraitser’s 2021 decision, in which, on every point of law and many of fact, she sided with the United States. The application to pursue this appeal was rejected by a single High Court judge, Swift, last June.

He permitted his rejection of the application to itself be appealed. That two-day hearing began Tuesday before Justice Jeremy Johnson and Dame Victoria Sharp.

The Timeline

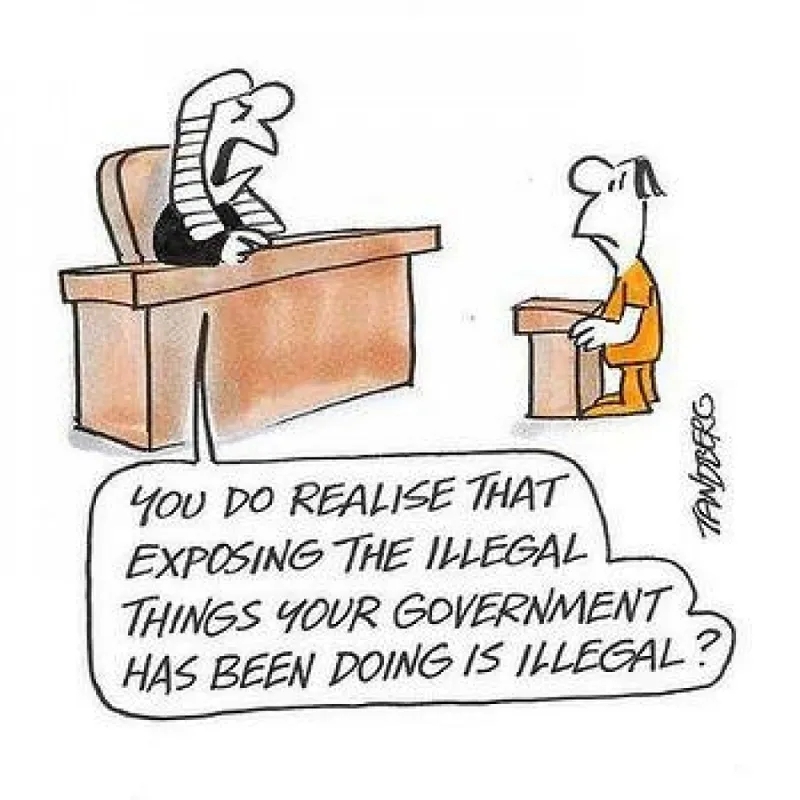

Assange lawyer Mark Summers made a forceful argument that the United States in essence is treating Assange no differently than any authoritarian regime would deal with a dissident journalist who revealed its secret crimes.

“There was evidence before the district judge that this prosecution was motivated to punish and inhibit the exposure of American state-level crimes,” Summers told the court. “There was unchallenged evidence” during Baraitser’s 2020 extradition hearing “of crimes that sit at the apex of criminality,” he said.

He said there was a direct nexus between Assange’s work to expose U.S. crimes and the U.S. pursuing him. “This is a prosecution for those disclosures,” he said. “There is a straight-line correlation between those disclosures and the prosecution, but the district judge (Baraitser) addressed none of this and neither did Swift.”

Summers then sketched out a timeline of events showing successive stages of motivation for the United States to go after Assange. “There was compelling circumstantial evidence why the U.S. brought this case,” he said.

First, he said, there was no prosecution of Assange (despite the Obama administration empaneling a grand jury) until 2016, when the International Criminal Court announced it would look into possible U.S. crimes in Afghanistan, following Assange’s disclosures. The U.S. then denounced him as a political actor.

Summers said “that morphed into plans to kill or rendition Assange” from the Ecuadorian embassy, where he had asylum, following the Vault 7 release of C.I.A. spying tools in 2017.

The then new C.I.A. Director Mike Pompeo, in his first public appearance in that position, denounced WikiLeaks as a hostile, non-state intelligence service, a carefully chosen legal term, Summers said, that permitted taking covert action against a target without Congressional knowledge.

Because these plans to kill or rendition Assange, asked for by President Donald Trump, raised alarms with White House lawyers, a legal prosecution was pursued as a way to determine where to put Assange if he were renditioned to the U.S., Summers said.

“This prosecution only emerged because of that rendition plan,” he said. “And the prosecution that emerged is selective and it is persecution.” It was selective because even though other outlets, such as Freitag and cryptome.org,, had published the unredacted diplomatic cables first, Assange was the only one charged.

“This is not a government acting on good faith pursuing a legal” path, he said……………………………………

Assange lawyer Edward Fitzgerald called espionage, with which Assange is charged, a “pure political offense.” The issue is crucial to Assange’s defense because the U.S.-U.K. Extradition Treaty bars extraditions for political offenses.

However, the Extradition Act, Parliament’s implementing legislation of the Treaty, does not mention political offenses. Baraitser ruled that the Act and not the Treaty should take precedence.

Assange’s team has been arguing that he is wanted for a political crime and therefore the extradition should not proceed. They argued that the Act bars extradition for “political opinion,” which they equate with “political offense.

A considerable amount of time in the five-hour hearing was thus spent by Assange’s lawyers making the point that Assange’s charges are political. Fitzgerald argued that Britain has extradition treaties with 158 nations and in all but two (Kuwait and the UAE), political offenses are barred.

Assange’s work was to influence and change U.S. policy, Fitzgerald said, therefore his work was political and he could not be extradited for his political views or opinions.

Informants!

Justices Johnson and Sharp appeared to be not extremely well-versed in the Assange case and seemed at times surprised by what they were hearing from Assange’s lawyers. But they had been prepared on the U.S. view of Assange allegedly harming U.S. informants.

What they didn’t know is that Assange had actually spent time redacting the names of U.S. informants from the Diplomatic Cables, while WikiLeaks‘ mainstream partners in 2010 did not.

Justice Johnson asked before lunch whether there were cases where someone had published the names of informants and were not prosecuted. After the break, Summers offered the example of Philip Agee, the ex-C.I.A. agent who revealed undercover agents’ names, some of whom were harmed, but he was never indicted for it.

Summers also mentioned The New York Times publishing names of informants in the Pentagon Papers. “The New York Times was never prosecuted,” Summers said. However, Richard Nixon indeed empaneled a grand jury in Boston to indict Times reporters but after it was revealed the government tapped whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg’s phone — and thus also the reporters’ — the case was dropped.

Despite their apparent unfamiliarity with the Assange case both judges seemed intrigued by its serious political, legal and press freedom issues. They are senior judges who might be less susceptible to political pressure.

The Death Penalty

The judges may also have been surprised to learn that under U.S. law and practice, (in this case with agreement from the British government), new charges could be added to Assange’s indictment after he would arrive in America. The Espionage Act, for instance, carries a provision for the death penalty if committed during wartime.

Britain does not have the death penalty and cannot extradite someone who could face capital punishment. Though the U.S. could offer Britain diplomatic assurances that it would not seek the death penalty against Assange, so far it has refused.

Fitzgerald also seemed to shock the courtroom by speaking of instances in U.S. courts where someone convicted for one crime could at sentencing receive time for another offense he or she was never tried for.

He expressed concern that though Assange was never charged with the Vault 7 C.I.A. leak, he might still be sentenced for it. He also said that at sentencing the rules of admissibility could be discarded, for example to consider evidence that was obtained through surveillance.

First Amendment

The judges may have been surprised to hear that the U.S. prosecutor in Virginia has said he may deny Assange his First Amendment rights during trial on U.S. soil because he is not a U.S. citizen. Pompeo stated more categorically that Assange would be without First Amendment protection.

Stripping the right of free speech is a violation of Article 10 of the European Court of Human Rights, Assange’s lawyers argued.

What Strasbourg Would Do

Summers brought the court through a scenario in which the European Court of Human Rights had tried Chelsea Manning, instead of a U.S. military court. He said whistleblower protection laws in Europe had advanced to the point where he believed the court would have weighed the harm done by breaking a confidentiality agreement and the harm prevented by blowing the whistle…….

The overall strategy of Assange’s lawyers appeared to be to make it obvious to these judges that there are vast grounds for appeal as well as arguments to toss the case (such as evidence of C.I.A. spying on Assange’s privileged conversations with his lawyers)

Forseeable

Assange’s lawyers also argued that Article 7 of the European Convention on Human Rights says someone must foresee that their behavior is a crime before he or she could be charged with it.

They said Assange could not have known that publishing his classified disclosures could have led to prosecution under the Espionage Act because no journalist or publisher had ever been charged under it for possession and publication of classified material. Therefore a violation of Article 7 should bar extradition, they say……………………

The hearing continues on Wednesday with lawyers representing the United States presenting their arguments about why Assange should not be allowed to appeal. https://consortiumnews.com/2024/02/20/day-one-assange-timeline-exposes-us-motives/

—

Why Australia should ditch the AUKUS nuclear submarine and-pivot-to-pitstop-power

Dr Elizabeth Buchanan is an expert associate of the ANU National Security College. This is an excerpt from the latest issue of Australian Foreign Affairs.

There is an elephant in the room, even though it is not a concern for current AUKUS leaders and key backers because it won’t need attention for a decade or so.

Nonetheless, the quandary exists, and we should acknowledge it: the SSN-AUKUS probably won’t materialise. Domestic tensions in both the US and UK are simmering away, with Washington already stating it has no plans to ever operate the boat.

Pillar One does have elements worth salvaging. The sale by Washington to Canberra of at least three Virginia-class SSNs from as soon as the early 2030s is reasonable. As is the exchange of expertise through the embedding of personnel and injection of capital into shipyard infrastructure. Increasing SSN visits to Australian ports by our UK and US partners via the Submarine Rotational Force West is also sensible. Indeed, the SRF-W should be put on steroids.

But the design and attempted construction of a future submarine – the SSN-AUKUS – should be scrapped. This would save us time and money, given the high likelihood the SSN-AUKUS won’t eventuate. With the US not intending to operate the SSN-AUKUS and committing to the SSN-X instead, Canberra is left to rely on London. This is precarious to say the least.

Canberra should focus its efforts on interoperability with the US in our maritime backyard. After all, Washington is geographically wedded to the same Pacific arena. It is clear our long-term regional maritime interests align more with Washington than with London.

We should acquire as intended the three Virginia-class subs and get behind the US’s SSN-X. If the UK fulfils the ambitious SSN-AUKUS project, it will likely share similar elements to the SSN-X in any case – not least the weapons and propulsion systems. Theoretically, Australia would provide maintenance and support for the UK’s SSN-AUKUS via SRF-W, as we will for the Virginia-class subs and probably for the SSN-X too.

This more sensible AUKUS pathway takes advantage of Australia’s pit-stop power. Our value proposition to partners is our enhanced ability to maintain and host their SSN capabilities, while also bringing our own capabilities to the table. Come 2030 and through to the 2040s, Australia’s SRF-W is likely to contain no less than five different submarine classes. We could see our trusty but aged Collins-class aside a single visiting British Astute, up to nine Virginias, as well as the SSN-X and, of course, the mystical SSN-AUKUS.

This is surely more submarine capability housed in the Indo-Pacific than the AUKUS partners could poke a stick at, which is good news for Canberra. Keeping the waters of the Indo-Pacific free from coercion and potentially armed conflict is a binding mutual interest for Australia, the US and the UK. This is also true for Australia’s global partners and allies, as maritime security challenges originating in the Indo-Pacific ripple across the globe. Of course, our competitors – and states we don’t see eye to eye with – also want the continued facilitation of maritime trade throughout the world. But the capabilities to marshal and control the world’s seas are strengthening and not necessarily in our favour, with vast military modernisation processes under way in our neighbourhood.

In the wise words of Sean Connery’s naval captain in The Hunt for Red October, “one ping” tells us only part of the picture. The optimal pathway tabled by AUKUS leaders is merely one approach to SSN capability for Australia. There are many options for achieving the right capability. We’ve committed to a pathway that has welcomed extremely limited consultation or public debate. One ping, one approach, offers only part of the picture.

Defence acquisition is an enduring process, involving constant review and revision. But even a capability novice must accept that pursuing a “Frankenstein” approach to delivering an SSN is beyond the pale in terms of risk. This is not a call to walk back on the plan to acquire nuclear-powered submarines.

As the island continent smack bang in the middle of the Indian and Pacific Ocean theatres, Australia cannot bunker down and avoid the fallout of sharpening competition on its doorstep. But nor should Canberra expect to sidestep the competition. As a net beneficiary of the extant rules-based order, secured and administered primarily by our partners, namely Washington, Australia ought to be providing security too.

For our allies and partners, Australia’s geography is unbeatable in an era of Indo-Pacific strategic competition. Our pit-stop power is a potential solution to a glaring problem: the SSN-AUKUS might not ever eventuate. While this would not necessarily be detrimental to Australia, we need an SSN capability. We can arrive at one by putting SRF-W at the centre of AUKUS, making the most of our pit-stop power to support the enhanced operation of partner SSN presence in our backyard, while continuing efforts to acquire and operate our own SSN capability. Any optimal pathway surely needs to be sensible too.

Swarming Our World. What Happens When Killer Robots Start Communicating with Each Other?

“Emergent” AI Behavior and Human Destiny

What Happens When Killer Robots Start Communicating with Each Other?

Tom Dispatch, Michael Klare, FEBRUARY 20, 2024

Make no mistake, artificial Intelligence (AI) has already gone into battle in a big-time way. The Israeli military is using it in Gaza on a scale previously unknown in wartime. They’ve reportedly been employing an AI target-selection platform called (all too unnervingly) “the Gospel” to choose many of their bombing sites. According to a December report in the Guardian, the Gospel “has significantly accelerated a lethal production line of targets that officials have compared to a ‘factory.’” The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) claim that it “produces precise attacks on infrastructure associated with Hamas while inflicting great damage to the enemy and minimal harm to noncombatants.” Significantly enough, using that system, the IDF attacked 15,000 targets in Gaza in just the first 35 days of the war. And given the staggering damage done and the devastating death toll there, the Gospel could, according to the Guardian, be thought of as an AI-driven “mass assassination factory.”

Meanwhile, of course, in the Ukraine War, both the Russians and the Ukrainians have been hustling to develop, produce, and unleash AI-driven drones with deadly capabilities. Only recently, in fact, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky created a new branch of his country’s armed services specifically focused on drone warfare and is planning to produce more than one million drones this year. According to the Independent, “Ukrainian forces are expected to create special staff positions for drone operations, special units, and build effective training. There will also be a scaling-up of production for drone operations, and inclusion of the best ideas and top specialists in the unmanned aerial vehicles domain, [Ukrainian] officials have said.”

And all of this is just the beginning when it comes to war, AI-style, which is going to include the creation of “killer robots” of every imaginable sort. But as the U.S., Russia, China, and other countries rush to introduce AI-driven battlefields, let TomDispatch regular Michael Klare, who has long been focused on what it means for the globe’s major powers to militarize AI, take you into a future in which (god save us all!) robots could be running (yes, actually running!) the show. Tom

By combining AI with advanced robotics, the U.S. military and those of other advanced powers are already hard at work creating an array of self-guided “autonomous” weapons systems — combat drones that can employ lethal force independently of any human officers meant to command them. Called “killer robots” by critics, such devices include a variety of uncrewed or “unmanned” planes, tanks, ships, and submarines capable of autonomous operation. The U.S. Air Force, for example, is developing its “collaborative combat aircraft,” an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) intended to join piloted aircraft on high-risk missions. The Army is similarly testing a variety of autonomous unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs), while the Navy is experimenting with both unmanned surface vessels (USVs) and unmanned undersea vessels (UUVs, or drone submarines). China, Russia, Australia, and Israel are also working on such weaponry for the battlefields of the future.

Michael Klare, Swarming Our World

POSTED ON FEBRUARY 20, 2024

Make no mistake, artificial Intelligence (AI) has already gone into battle in a big-time way. The Israeli military is using it in Gaza on a scale previously unknown in wartime. They’ve reportedly been employing an AI target-selection platform called (all too unnervingly) “the Gospel” to choose many of their bombing sites. According to a December report in the Guardian, the Gospel “has significantly accelerated a lethal production line of targets that officials have compared to a ‘factory.’” The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) claim that it “produces precise attacks on infrastructure associated with Hamas while inflicting great damage to the enemy and minimal harm to noncombatants.” Significantly enough, using that system, the IDF attacked 15,000 targets in Gaza in just the first 35 days of the war. And given the staggering damage done and the devastating death toll there, the Gospel could, according to the Guardian, be thought of as an AI-driven “mass assassination factory.”

Meanwhile, of course, in the Ukraine War, both the Russians and the Ukrainians have been hustling to develop, produce, and unleash AI-driven drones with deadly capabilities. Only recently, in fact, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky created a new branch of his country’s armed services specifically focused on drone warfare and is planning to produce more than one million drones this year. According to the Independent, “Ukrainian forces are expected to create special staff positions for drone operations, special units, and build effective training. There will also be a scaling-up of production for drone operations, and inclusion of the best ideas and top specialists in the unmanned aerial vehicles domain, [Ukrainian] officials have said.”

And all of this is just the beginning when it comes to war, AI-style, which is going to include the creation of “killer robots” of every imaginable sort. But as the U.S., Russia, China, and other countries rush to introduce AI-driven battlefields, let TomDispatch regular Michael Klare, who has long been focused on what it means for the globe’s major powers to militarize AI, take you into a future in which (god save us all!) robots could be running (yes, actually running!) the show. Tom

“Emergent” AI Behavior and Human Destiny

What Happens When Killer Robots Start Communicating with Each Other?

Yes, it’s already time to be worried — very worried. As the wars in Ukraine and Gaza have shown, the earliest drone equivalents of “killer robots” have made it onto the battlefield and proved to be devastating weapons. But at least they remain largely under human control. Imagine, for a moment, a world of war in which those aerial drones (or their ground and sea equivalents) controlled us, rather than vice-versa. Then we would be on a destructively different planet in a fashion that might seem almost unimaginable today. Sadly, though, it’s anything but unimaginable, given the work on artificial intelligence (AI) and robot weaponry that the major powers have already begun. Now, let me take you into that arcane world and try to envision what the future of warfare might mean for the rest of us.

By combining AI with advanced robotics, the U.S. military and those of other advanced powers are already hard at work creating an array of self-guided “autonomous” weapons systems — combat drones that can employ lethal force independently of any human officers meant to command them. Called “killer robots” by critics, such devices include a variety of uncrewed or “unmanned” planes, tanks, ships, and submarines capable of autonomous operation. The U.S. Air Force, for example, is developing its “collaborative combat aircraft,” an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) intended to join piloted aircraft on high-risk missions. The Army is similarly testing a variety of autonomous unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs), while the Navy is experimenting with both unmanned surface vessels (USVs) and unmanned undersea vessels (UUVs, or drone submarines). China, Russia, Australia, and Israel are also working on such weaponry for the battlefields of the future.

The imminent appearance of those killing machines has generated concern and controversy globally, with some countries already seeking a total ban on them and others, including the U.S., planning to authorize their use only under human-supervised conditions. In Geneva, a group of states has even sought to prohibit the deployment and use of fully autonomous weapons, citing a 1980 U.N. treaty, the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, that aims to curb or outlaw non-nuclear munitions believed to be especially harmful to civilians. Meanwhile, in New York, the U.N. General Assembly held its first discussion of autonomous weapons last October and is planning a full-scale review of the topic this coming fall.

For the most part, debate over the battlefield use of such devices hinges on whether they will be empowered to take human lives without human oversight. Many religious and civil society organizations argue that such systems will be unable to distinguish between combatants and civilians on the battlefield and so should be banned in order to protect noncombatants from death or injury, as is required by international humanitarian law. American officials, on the other hand, contend that such weaponry can be designed to operate perfectly well within legal constraints.

However, neither side in this debate has addressed the most potentially unnerving aspect of using them in battle: the likelihood that, sooner or later, they’ll be able to communicate with each other without human intervention and, being “intelligent,” will be able to come up with their own unscripted tactics for defeating an enemy — or something else entirely. Such computer-driven groupthink, labeled “emergent behavior” by computer scientists, opens up a host of dangers not yet being considered by officials in Geneva, Washington, or at the U.N.

For the time being, most of the autonomous weaponry being developed by the American military will be unmanned (or, as they sometimes say, “uninhabited”) versions of existing combat platforms and will be designed to operate in conjunction with their crewed counterparts. While they might also have some capacity to communicate with each other, they’ll be part of a “networked” combat team whose mission will be dictated and overseen by human commanders. The Collaborative Combat Aircraft, for instance, is expected to serve as a “loyal wingman” for the manned F-35 stealth fighter, while conducting high-risk missions in contested airspace. The Army and Navy have largely followed a similar trajectory in their approach to the development of autonomous weaponry.

The Appeal of Robot “Swarms”

However, some American strategists have championed an alternative approach to the use of autonomous weapons on future battlefields in which they would serve not as junior colleagues in human-led teams but as coequal members of self-directed robot swarms. Such formations would consist of scores or even hundreds of AI-enabled UAVs, USVs, or UGVs — all able to communicate with one another, share data on changing battlefield conditions, and collectively alter their combat tactics as the group-mind deems necessary.

“Emerging robotic technologies will allow tomorrow’s forces to fight as a swarm, with greater mass, coordination, intelligence and speed than today’s networked forces,” predicted Paul Scharre, an early enthusiast of the concept, in a 2014 report for the Center for a New American Security (CNAS). “Networked, cooperative autonomous systems,” he wrote then, “will be capable of true swarming — cooperative behavior among distributed elements that gives rise to a coherent, intelligent whole.”

As Scharre made clear in his prophetic report, any full realization of the swarm concept would require the development of advanced algorithms that would enable autonomous combat systems to communicate with each other and “vote” on preferred modes of attack. This, he noted, would involve creating software capable of mimicking ants, bees, wolves, and other creatures that exhibit “swarm” behavior in nature. As Scharre put it, “Just like wolves in a pack present their enemy with an ever-shifting blur of threats from all directions, uninhabited vehicles that can coordinate maneuver and attack could be significantly more effective than uncoordinated systems operating en masse.”

In 2014, however, the technology needed to make such machine behavior possible was still in its infancy. To address that critical deficiency, the Department of Defense proceeded to fund research in the AI and robotics field, even as it also acquired such technology from private firms like Google and Microsoft. A key figure in that drive was Robert Work, a former colleague of Paul Scharre’s at CNAS and an early enthusiast of swarm warfare. Work served from 2014 to 2017 as deputy secretary of defense, a position that enabled him to steer ever-increasing sums of money to the development of high-tech weaponry, especially unmanned and autonomous systems.

From Mosaic to Replicator

Much of this effort was delegated to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Pentagon’s in-house high-tech research organization. As part of a drive to develop AI for such collaborative swarm operations, DARPA initiated its “Mosaic” program, a series of projects intended to perfect the algorithms and other technologies needed to coordinate the activities of manned and unmanned combat systems in future high-intensity combat with Russia and/or China…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

To obtain both the hardware and software needed to implement such an ambitious program, the Department of Defense is now seeking proposals from traditional defense contractors like Boeing and Raytheon as well as AI startups like Anduril and Shield AI. While large-scale devices like the Air Force’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft and the Navy’s Orca Extra-Large UUV may be included in this drive, the emphasis is on the rapid production of smaller, less complex systems like AeroVironment’s Switchblade attack drone, now used by Ukrainian troops to take out Russian tanks and armored vehicles behind enemy lines.

At the same time, the Pentagon is already calling on tech startups to develop the necessary software to facilitate communication and coordination among such disparate robotic units and their associated manned platforms. To facilitate this, the Air Force asked Congress for $50 million in its fiscal year 2024 budget to underwrite what it ominously enough calls Project VENOM, or “Viper Experimentation and Next-generation Operations Model.” Under VENOM, the Air Force will convert existing fighter aircraft into AI-governed UAVs and use them to test advanced autonomous software in multi-drone operations. The Army and Navy are testing similar systems.

When Swarms Choose Their Own Path

In other words, it’s only a matter of time before the U.S. military (and presumably China’s, Russia’s, and perhaps those of a few other powers) will be able to deploy swarms of autonomous weapons systems equipped with algorithms that allow them to communicate with each other and jointly choose novel, unpredictable combat maneuvers while in motion. Any participating robotic member of such swarms would be given a mission objective (“seek out and destroy all enemy radars and anti-aircraft missile batteries located within these [specified] geographical coordinates”) but not be given precise instructions on how to do so. That would allow them to select their own battle tactics in consultation with one another. If the limited test data we have is anything to go by, this could mean employing highly unconventional tactics never conceived for (and impossible to replicate by) human pilots and commanders.

…………………………………… In military terms, this means that a swarm of autonomous weapons might jointly elect to adopt combat tactics none of the individual devices were programmed to perform — possibly achieving astounding results on the battlefield, but also conceivably engaging in escalatory acts unintended and unforeseen by their human commanders, including the destruction of critical civilian infrastructure or communications facilities used for nuclear as well as conventional operations………………………………………………..

What then? Might they choose to keep fighting beyond their preprogrammed limits, provoking unintended escalation — even, conceivably, of a nuclear kind? Or would they choose to stop their attacks on enemy forces and instead interfere with the operations of friendly ones, perhaps firing on and devastating them

……………………………….. Many prominent security and technology officials are, however, all too aware of the potential risks of this “emergent behavior” in future robotic weaponry and continue to issue warnings against the rapid utilization of AI in warfare.

Of particular note is the final report that the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence issued in February 2021. Co-chaired by Robert Work (back at CNAS after his stint at the Pentagon) and Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google, the commission recommended the rapid utilization of AI by the U.S. military to ensure victory in any future conflict with China and/or Russia. However, it also voiced concern about the potential dangers of robot-saturated battlefields……………………………………………………………..

When the leading advocates of autonomous weaponry tell us to be concerned about the unintended dangers posed by their use in battle, the rest of us should be worried indeed. Even if we lack the mathematical skills to understand emergent behavior in AI, it should be obvious that humanity could face a significant risk to its existence, should killing machines acquire the ability to think on their own…………… more https://tomdispatch.com/emergent-ai-behavior-and-human-destiny/—

Utility EdF Writes Down $14B Loss on Delayed UK Nuclear Megaproject

By Peter Reina, February 20, 2024, https://www.enr.com/articles/58180-utility-edf-writes-down-14b-loss-on-delayed-uk-nuclear-megaproject

Following recent news of additional delays and cost hikes on the U.K.’s 3,260-MW Hinkley Point C nuclear power plant, the project company has reported an impairment of $14 billion on its assets.

French state controlled utiilty firm Electricité de France (EdF), which controls project financing and construction, last month updated Hinkley Point C’s forecast completion to between 2029 and 2031, with costs rising to a range of $39-43 billion. The previous completion target set in May 2022 was June 2027. EdF is currently financing all project construction costs.

Announcing its 2023 annual report, the utility also set this March as the expected target date for fuel loading at its 1,650-MW Flamanville 3 nuclear power plant on the north French coast. When work started in 2007, fuel loading was forecast for 2011.