TODAY “Churnalism” – that is a timely word that we all need to consider

The days of independent investigative journalism as a well-paid job – are pretty much over .

We get our “mainstream” news from journalists who are toeing the line of the corporate media owners, and of government.

I’m grateful to DES FREEDMAN, who today introduced me to that lovely word “churnalism”. How beautifully it expresses all the joyous news that bombards us, about the wonderful world of militarism, and its exciting new devices for killing! Such a glorious use of our taxes!

However, I’m not all that thrilled to learn of the horrible deaths to be inflicted upon Russian and Chinese human beings, as some kind of compensation for my own horrible death in World War 3. Indeed, I’m quite puzzled at the prevailing patriotic view that belligerence and confrontation are the way to go , with these other countries, whom we are somehow obliged to hate.

Of course, the really hard tasks are apparently just too hard to contemplate – those difficult things like negotiation, diplomacy, compromise……….. Especially if it’s dealing with people whose native language is not English. We barely tolerate the Europeans, (but of course, we make an exception for the Ukrainians as they are willingly sacrificing themselves in the cause of American hegemony).

A few brave souls are still doing objective journalism, either openly, or sort of “between the lines” as they write about political tensions, about international conflicts, – and they hope to hang on to their jobs in the “respectable” media.

Meanwhile – where the real journalism is now happening, where questions are really being asked, is in the “alternative ” media – that depends on the generosity of volunteers, giving their time, some voluntary subscribers – but no funding from government and corporate advertising .

I’m not sure that these alternative voices are going to cut through the miitaristic handouts that are regurgitated in the prevailing churnalism, as well as in the jungle of “social” media.

The questions that need to be asked and answered are so simple and obvious – that somehow by some magical veil thrown over our eyes – they are just never allowed to be seen:

- is it a good idea to provoke Putin?

- is it a good idea to attack China About Taiwan?

- why is our tax-payer money going into ever more terrible weapons?

- why is it not going into healthcare?

- why is it not going into education? to helping the homeless? to preserving the environment?

So – the military juggernaut rolls on. Facebook, Instagram, Mastodon etc now censor links to the irregular media, where such questions are asked. So I don’t know whether sensible thinking will ever rise to the surface above the churnalism.

If it doesn’t – we are all doomed.

Too big to fail? Who cares if there’s no accountability – the Nuclear Lie

How is it that political parties can get away promising huge projects that won’t eventuate for 10 to 20 years; that’s four to eight election cycles in the future.

Even if the current opposition leader, Peter Dutton, manages to sell the nuclear dream at the next election, he won’t be around to see his promises are kept. He simply isn’t accountable for the claims he’s making today.

by David Salt | Aug 21, 2024 https://sustainabilitybites.com/too-big-to-fail-who-cares-if-theres-no-accountability/

Building big on big promises of endless clean energy ignores the limits of our institutions. It’s something rarely considered in the febrile, volatile environment of contemporary politics. We pull our leaders up on the smallest of inconsistencies but let them get away with the biggest of lies. When you next cast your vote, keep in mind that extraordinary promises require extraordinary accountability.

The nuclear lie

Australia is currently contesting a future based on nuclear energy vs renewables.

The conservative opposition Coalition has put forward a ‘plan’ to build seven government-owned nuclear plants across Australia that will come online around 2035. The promise is that these plants will provide cheap, reliable carbon free electricity and help our nation achieve ‘net zero’ by 2050. It’s a strange policy requiring massive government investment and control from a party the stands for smaller government. But that’s just the beginning of strangeness around this thinking.

To call it a ‘plan’ is drawing a long bow because the proposal comes with no costings or modelling attached; existing legislation prevents the construction of nuclear power plants; and Australia currently lacks the necessary capacity to develop a nuclear power network (something the nuclear loving coalition did nothing about while in government for most of the last decade). Experts from across Australia don’t believe it would be possible to build the plants by 2035, or that they can produce electricity at anything close to what can be produced by renewables.

However, if the electorate was to buy the proposal and vote in the conservatives, it would result in the extension of coal power (to fill the gap till nuclear comes online), the expansion of gas energy and a redirection of investment away from renewables, which don’t really complement nuclear anyway.

While questions are being asked about all of these uncertainties, I think a more fundamental issue relates to governance and scales of time.

How is it that political parties can get away promising huge projects that won’t eventuate for 10 to 20 years; that’s four to eight election cycles in the future. Even if the current opposition leader, Peter Dutton, manages to sell the nuclear dream at the next election, he won’t be around to see his promises are kept. He simply isn’t accountable for the claims he’s making today.

Flawed accountability

Clearly this is a weakness of our democratic system of governance. We vote someone in to represent us for a number of years, three to six years in most electorates around the world, and we hold these representatives to account for the how they perform in delivering what they promised at election time. This tends to have voters actively reflecting on day-to-day business (taxes, health care delivery, education etc), while simply ignoring the hundreds of billions of dollars of commitments made for promises that sit well over the electoral horizon (promises like nuclear submarine fleets and nuclear power plants).

This weakness in accountability appears to be increasingly exploited by all sides of politics. Voters are collapsing under the ‘cost of living’, holding their breaths with every quarterly inflation announcement, and quick to pull down any politician who seems insensitive to the needs of ‘working families’.

Yet, at the same time, voters seem oblivious to the consequences of political leaders making a $100 billion dollar pledge to be delivered in 3-4 election’s time (though I note critics say this plan could easily end up costing as much as $600 billion). Consequently, we’re seeing more of these big announcements because the pollies know the electorate is not going to hold them to account. They simply don’t have the capacity to take it in, they are too absorbed by the day-to-day stuff.

Extraordinary accountability

The late, great astronomer Carl Sagan once said that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”. He was referring to the possibility of UFOs and extra-terrestrial life, but the same principle should apply to extraordinary political promises. If a political leader makes an extraordinary promise that can’t be delivered in one to two electoral cycles and commits vast quantities of (scarce) resources, then they need to put up a corresponding level of ‘extraordinary accountability’ before their case should be considered seriously by the broader electorate.

It’s not just the money involved and skills needed, it’s also how such a goal might be met over several electoral cycles. Bipartisan support, you would think, would have to be a basic first step.

A couple of decades ago Prime Minister John Howard passed the Charter of Budget Honesty Act in an effort to make political parties more accountable for the spending they promised. Many claim it has achieved little however, at the very least, it was an effort to show the electorate that politicians were aware that they needed to demonstrate greater accountability for the promises they make.

In the case of Dutton’s nuclear plan, this accountability is completely missing. However, rather than acknowledging this and attempting to build a stronger case, the Coalition has instead been attacking the institutions that have been examining the proposal (like CSIRO and the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering). The conservatives have simply written them off when they question the validity of the proposal. (“I’m not interested in the fanatics,” says Dutton.) This doubling down is doubly dumb because it involves both extraordinary promises with no proof and the politicisation of independent experts.

Beyond nuclear

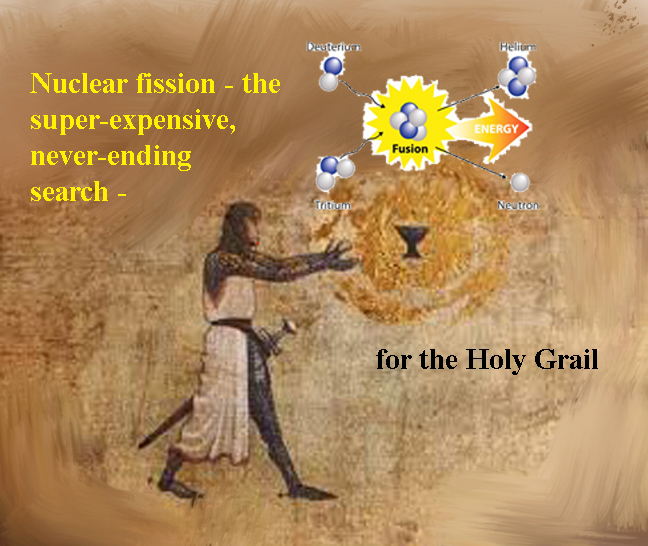

But this tendency to aim extraordinarily big without extraordinary accountability goes way beyond Australia’s future nuclear energy ambitions. Consider the quest for fusion energy.

Europe is chasing the holy grail of clean energy by investing in fusion power. The multi-country International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project was dreamt up in the 1980s and took over 25 years to come together as a formal collaboration between China, the European Union, India, Japan, South Korea, Russia, and the United States. Construction began in 2010 with operations expected to start about a decade later. But manufacturing faults, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the complexity of a first-of-a-kind machine (one of the most complex machines in the world) have all slowed progress and now ITER will not turn on until 2034, 9 years later than currently scheduled. Energy producing fusion reactions—the goal of the project—won’t come online until 2039!

ITER is a doughnut-shaped reactor, called a tokamak, in which magnetic fields contain a plasma of hydrogen nuclei hot enough to fuse and release energy. The technocrats running the project will gleefully explain that particle beams and microwaves heat the plasma to 150 million degrees Celsius—10 times the temperature of the Sun’s core—while a few meters away the superconducting magnets must be cooled to minus 269°C, a few degrees above absolute zero. Amazing as that sounds, it’s possibly less challenging than coordinating the actions and investment choices of the world’s superpowers decades into the future; Russia, China and the US are not exactly buddies at the moment. How strong do the ‘particle beams’ have to be to hold this agreement together for 20-30 years.

And even if ITER never eventuates, the possibility of ‘unlimited, clean energy’ over the horizon impacts investment decisions today. We’re seeing this even with the nuclear fission debate today in Australia as investors become wary of putting their money into renewables with the opposition promising nuclear powerplants just down the road.

And then there’s growing talk about implementing geoengineering solutions to fix humanity’s existential overheating problem (‘global boiling’). We’re talking pumping sulphates into the stratosphere, giant mirrors in space and fertilising the ocean to draw down carbon in the atmosphere. Playing God by ‘controlling’ the Earth system is going to be as big a governance issue as it is a technical challenge. And, given we’re doing so poorly on energy solutions using technology that’s relatively well understood, we’d be wise to demand extraordinary accountability before swallowing any promises in this domain.

Going thermonuclear

Which is not to say that ‘thermonuclear’ is not potentially a big part of a possible energy solution, just not the man-made kind. That big ball of energy in the sky called the Sun is driven by thermonuclear fusion, and this energy is there for the harvesting via photovoltaic cells (and indirectly by wind turbines).

And the accountability on these renewable sources of power doesn’t need the same level of extraordinary accountability that nuclear and thermonuclear demands because it can be delivered now, in the same electoral cycle as the promise to deliver it.

Renewables are not without their own set of issues but in terms of cost, feasibility AND accountability, it’s a solution that Australia (and the world) should be implementing now. Renewables are not ‘too big to fail’ but waiting twenty years before switching to them is simply too little too late.