There’s a gaping hole in Dutton’s nuclear plan. He says it’s Albanese’s problem to solve.

“With Dad’s eyesight, it was a gradual process,” Lester says. “By three, four years after ’53 he was completely blinded, then, by those nuclear tests. So there was a lot of fear, there was a lot of sickness. And there weren’t a lot of answers of what the hell happened in 1953.”

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this article contains names and photos of people who have died.

The Age By Julia Carr-Catzel, 11January 12, 2025

When Opposition Leader Peter Dutton proposed nuclear energy reactors on almost every mainland state last year, he reignited divisive public debate. It’s a debate Indigenous Australians are likely to be at the heart of.

It is little acknowledged that Australia’s nuclear story is largely an Indigenous one. It starts in the 1950s, when radioactive fallout from bomb tests silently settled over Aboriginal communities that were not adequately protected by the government of the day. It encompasses the very beginning of the nuclear cycle: the mining of uranium, to its end – the storage of nuclear waste.

The intergenerational fear of radioactive contamination and distrust of government is fuelling community opposition, particularly among some traditional landowners, to a potential nuclear energy industry here in Australia. And it’s why every proposal for a national nuclear waste repository across the country has, so far, failed.

The nuclear waste problem is unavoidably tied to nuclear energy reactors, a cornerstone of Dutton’s energy policy for 2025. Nuclear waste will also be a major challenge for future governments as they inherit radioactive waste from AUKUS submarines.

Emu Field, 1950s

Karina Lester speaks from her brightly lit office in central Adelaide. She comes from Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara lands at a homeland called Walatina. “The country is quite stunning, actually. There’s lots of woodland area, so mulga acacias growing there, but there’s beautiful sand dunes through that country and where my late father Yami was born is a creek called Walkinytjanu Creek, which is a beautiful spot as well.”

Lester is describing a special part of the South Australian outback, a 12-hour drive north of Adelaide, where her father, Yami Lester, worked for pastoralists. But on October 15, 1953, Yami, who was only a young boy at the time, playing in the dunes noticed something above.

“That morning was when they felt the ground shake, and the black mist roll. And one thing many of my old people had spoken about was the fact that this black mist rolled silently, so it came with no wind or no, you know, picking up sticks and leaves and grasses. And it didn’t come with a noise like dust storms do. It travelled silently. And it was that that was the real fear. They knew how country operated and worked. But this one was very different.”

What Yami and his family peered up at were the remnants of a giant mushroom cloud from a nuclear weapons test in Emu Field, about a six hour-drive south-west of Walatina.

“Nana recalls a very strong stench to it like a really oily toxic smell and that oil had fallen over the plants, you know, over the trees. Within hours, oranges withered. So, nana mob were digging holes in the sand dunes and trying to bury the children and hide them and protect them.”

Operation Totem was the first of two major nuclear weapons tests conducted by the British in Emu Field, signed off by the Menzies government. It was the 1950s, the beginning of the Cold War. Britain was developing its nuclear capabilities and the Australian outback was the perfect location with its vast remoteness.1

Emu Field was the location of just two of 12 major weapons trials across Australia, and hundreds of minor trials until the 1960s. Some nuclear bombs had a kiloton yield as large as that of Hiroshima.

“Within hours of that toxic fallout, people became really sick … There was panic because that oily sort of black mist rolling put people into panic. And then, of course, people’s eyes became really sore and red and pussy. Nana had skin rashes on her shins, people became really sick, like a lot of the elderly.”

Decades later, in 1985, the McClelland Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia concluded that: “Inadequate resources were allocated to guaranteeing the safety of Aboriginal people.” Commissioners concluded the one native patrol officer on duty had an impossible task of locating and warning Aboriginal people scattered over more than 100,000 square kilometres.

“It was tough as it was there, being in 1953, working on a pastoral property, let alone trying to understand what government of the day was going to do,” says Lester. “And then, all of a sudden, experience what happened, without any control or knowledge or understanding.”

Aboriginal people were not the only victims. Aircrews flew through radioactive clouds and scientists walked around sites with minimal protective clothing, sometimes none at all.

“With Dad’s eyesight, it was a gradual process,” Lester says. “By three, four years after ’53 he was completely blinded, then, by those nuclear tests. So there was a lot of fear, there was a lot of sickness. And there weren’t a lot of answers of what the hell happened in 1953.”

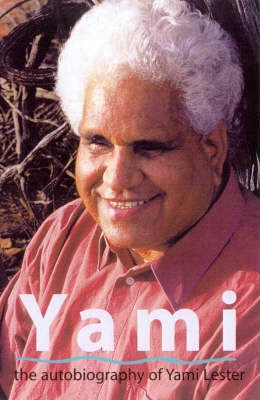

Yami dedicated his life to Aboriginal activism. His case was pivotal to the McClelland royal commission, although the commission could not link radiation to health issues, including establishing the cause of Yami’s blindness. Yami died, aged 75, in 2017.

“It was something that I always miss,” Lester says. “That he’d never really seen me grow up, he saw me in a different way of growing up with his disability, of course.”

The government commissioned a study in the 1990s into the link between Australia’s nuclear testing, including that at Emu Field, and the number of cancer cases among mostly military personnel. It didn’t establish a direct link between cancer cases and radiation exposure, but the study did find the mortality and cancer rate were higher than that of the general population.

In Woomera, 600 kilometres downwind of the tests, is a grave where 23 stillborn babies delivered in the years following the tests are buried, according to a class action case against the British Ministry of Defence.

“And there’s not really a lot of data around the health of people. If you look back in clinic records, perhaps at Yalata, or even Oak Valley, there was a period of time that there was a high spike for thyroid cancers. And people have passed now.”

Britain agreed to contribute £20 million towards a $100 million clean-up of Maralinga, the largest and most used site, and modest clean-up efforts were undertaken at the other sites. The Australian government paid $13.5 million to the Indigenous people of Maralinga as compensation for contamination of the land…………………………..

The government nuclear safety watchdog says it conducts regular safety checks and is committed to building trust with Maralinga Tjarutja peoples to feel confident to live on and engage with their land. But Lester says that trust may take a while to build. “There’s a whole lot of data missing around the safety of our environment and our traditional lands [in Emu Field]. And so, you know, we need to look at the path of where Totem 1 had fallen over, which is Walatina, and how safe is it there? You know: what’s in the dust, what’s in the soil? What’s in our waters? How safe are our trees?

“Because we still go digging for witchetty grubs, and we go eating the animals like goannas and perenties, and turkeys, and, you know, we still practise those things because that’s part of our Anangu culture. So it’s the unknown, that is the fear for us.”

When Dutton announced plans for a nuclear reactor on nearly every mainland state, Lester felt fearful again. It came on top of bipartisan support for the AUKUS deal, which locks Australia into storing high-level nuclear waste. “What’s going to happen when you have agreements like the AUKUS agreement?” Lester says. “You know, it’s a real fear for us … the waste of, you know, the UK and the US coming to potentially South Australia, or anywhere in Australia.”

Lester has, like her father, dedicated her adult life to activism. In 2023 , she represented the Australian wing of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, at the United Nations in New York. She says she will be at the forefront of community opposition. “Our government of the day has a level of responsibility. It is negligent of them to be sticking waste out in community that they think is out of sight, out of mind. Like the industry has completely outdone itself, like yes, it does all these amazing things. But you haven’t worked out your waste solution.

“And the solution that you put on the table constantly to First Nations peoples is stick it in your traditional lands. No, we say ‘no’ to nuclear waste, full stop.”

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Australia stores some of its low and intermediate-level nuclear waste at Lucas Heights, the Sydney suburb home to the country’s only nuclear reactor. Now a radioactive medicine factory, it produces products such as the dye injected into patients for scans to monitor cancers.

Australia has accumulated about 5000 cubic metres of intermediate radioactive waste, about two Olympic-sized swimming pools, and five more pools’ worth of low-level waste.

………………………. “The Commonwealth government has been struggling for 20 years to find a site for permanent storage of low-level waste,” says Ian Lowe, emeritus professor at the School of Environmental Science at Griffith University in Queensland. He has dedicated his life to studying energy supply and sustainability, and has written books on nuclear technology and its role in the energy mix.

Lowe says that the nuclear energy reactors Dutton wants built will produce high-level nuclear waste, requiring disposal in deep geological layers, several hundred metres underground.

……………………………………………………. “The Indigenous community is permanently scarred by the experience of the bomb tests in rural South Australia and the harm that came to some people as a result of those. And every proposal by the Commonwealth government for a low-level waste storage has been resisted by the local Indigenous community,” says Lowe.

“So if we began to set up a site to manage intermediate level waste and high-level waste in the long term, there will have to be very delicate and sensitive negotiations with Indigenous communities to get their permission for an activity like that on their land.”

The Kimba decision

There have been numerous attempts at establishing a national nuclear waste repository in Australia since the late 1990s. The most recent failed nuclear waste depository was in Kimba, a five-hour drive north-west of Adelaide and with a population of just over 1000.

The Kimba proposal became a bureaucratic nightmare, spanning eight years and rife with community divisiveness.

…………………………………………………………………………………… Challenges ahead

Australia’s almost 40-year-history of failed nuclear waste development proposals is less than encouraging for the Coalition’s hopes of a nuclear energy future.

There have been decades of development proposals for a centralised, national nuclear waste repository in states and territories across the country, including Woomera in South Australia in 2004, Muckaty Station in the Northern Territory in 2014, Flinders Ranges in South Australia in 2019, and most recently Kimba. Not one proposal has succeeded.

……………………………………… The failed Kimba project highlights the overwhelming challenge for governments after nearly a decade spanning three ministers, of site assessment and selection, landowner and community consultation and consent, Senate committee hearings and inquiries, legal challenges at state and local levels and countless regulatory hurdles.

And that’s just for a waste repository, at the end of the nuclear fuel cycle, let alone the infrastructure planning needed for a nuclear energy reactor itself.

Dutton says he wants this year’s election to be “a referendum on energy”……………… more https://www.theage.com.au/environment/sustainability/there-s-a-gaping-hole-in-dutton-s-nuclear-plan-he-says-it-s-albanese-s-problem-to-solve-20241113-p5kqe4.html

No comments yet.

Leave a comment