‘Inadequate’: Audit call on $368bn AUKUS cost estimate.

COMMENT. Even the Australian is being critical of AUKUS.

They don’t mention that the $368 billion doesn’t cover a high level nuclear waste dump and associated transport, or upgrades needed for the LeFevre peninsula to host a sub building facility at Osborne.

Some of Australia’s top naval experts have cast doubt on the government’s $368bn AUKUS price tag, warning that the cost will be ‘significantly more’.

Ben Packham The Australian 17.11.25

Some of Australia’s top naval experts have cast doubt on the government’s $368bn AUKUS price tag, saying the program to acquire two classes of nuclear-powered submarines will cost “significantly more” than originally thought, with higher upfront outlays.

UNSW Canberra’s naval studies group has called for an urgent and comprehensive audit of AUKUS costs “to provide a realistic financial baseline” for the program, which is already cannibalising the wider defence budget.

Labor argues it can fund the program without a major increase in defence funding beyond its currently planned outlays, which are set to rise from about 2 per cent of GDP to 2.33 per cent by 2033-34.

UNSW Canberra’s new Maritime Strategy for Australia warns the proposed expenditure “will likely be inadequate” to deliver on the government’s naval ambitions. “This is already evidenced by cuts to lower priority projects and sustainment,” the strategy says.

It argues the AUKUS ‘Pillar I’ submarine program “was not comprehensively costed at the outset and its full demand on the Defence budget is still to be fully quantified”.

The paper says a substantial increase to defence funding will be needed, urging the government to “conduct a comprehensive, independently verified costing of AUKUS Pillar I as a matter of urgency to allow for re-baselining of Defence financial requirements and recalculation of required overall Defence funding”.

The strategy also sounds the alarm over the navy’s “long-neglected” mine countermeasures and undersea mapping capabilities, saying they pose “a critical gap that must be regenerated to guarantee maritime access to ports and littoral (coastal) waters”.

It comes amid a Defence-wide cost-cutting drive, revealed by The Australian, that has forced service chiefs to slash sustainment budgets, reduce “rates of effort”, and look at axing some capabilities.

Former RSL president Greg Melick took aim at the funding issue last week, using his Remembrance Day speech to warn hat the nation’s military preparedness was being undermined. The speech earned him a rebuke from Paul Keating, who branded him a “dope” and accused him of seeking a war with China.

But retired Vice-Admiral Peter Jones endorsed Major General Melick’s warning, saying the stretched defence budget was “the elephant in the room at the moment”.

Admiral Jones, the lead author of the maritime strategy and head of the Australian Naval Institute, told The Australian: “It appears the cost (of AUKUS) is significantly more than what was originally thought, including greater upfront costs before submarine construction.”

The paper comes as the government finalises its updated defence strategy and capability investment program, both of which will be released ahead of next year’s federal budget.

Labor announced a $12bn upgrade to Western Australia’s shipbuilding precinct in recent weeks as a downpayment on AUKUS infrastructure in the state, which is likely to cost more than twice that figure.

Workforce costs are also soaring as hundreds of Australian sailors take up training places on US and British submarines, and Australian tradespeople are deployed to shipyards in both countries to gain experience building nuclear boats.

Defence Minister Richard Marles revealed the government’s $368bn AUKUS cost estimate two years ago when he announced the program’s “optimal pathway” to obtain three to five Virginia-class submarines from the US and a new class of AUKUS submarines to be built in Adelaide. He said this was equivalent to about “0.15 per cent of GDP for the life of the program”.

The Australian asked the minister’s office how the figure was arrived at, whether it had any statistical measure of its likely accuracy, and whether it would seek an independent assessment of the program’s cost. It declined to respond to all three questions.

A spokeswoman for Mr Marles instead issued a boilerplate statement repeating the government’s case for acquiring nuclear submarines.

“The acquisition of conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines for the Australian Defence Force is a multi-decade opportunity, representing the single biggest capability acquisition in our nation’s history and creating around 20,000 direct jobs over the next 30 years,” she said.

“Working with our AUKUS partners, Australia is not just acquiring world-leading submarine technology but building a new sovereign production line, supply chain and sustainment capability here in Australia. This includes growing the capabilities, capacity and resilience of business – particularly small and medium-sized enterprises.

What Australia can learn from China to become the world’s ‘cleaner’ rare earth refiner.

“People don’t quite grasp how much waste we’re talking about.”……………………… cases of cancers, arsenic poisoning and birth and joint deformities linked to years of unregulated dumping.

By Libby Hogan and Xiaoning Mo, Sat 15 Nov, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-11-15/australia-refining-rare-earths-environmental-challenges/105969994?utm_source=abc_news_app&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_campaign=abc_news_app&utm_content=other

Australia holds a plethora of rare earths — minerals essential for all sorts of cutting-edge technologies from wind turbines to hypersonic missiles.

Until now, most of them have been sent to be refined in China.

That is largely because the process is dirty, expensive, and politically unpopular.

But after last month signing a $13 billion critical minerals deal with the United States to boost production and refining, Australia must deal with some significant environmental challenges — mostly around water.

Marjorie Valix, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of Sydney, who researches sustainable mineral processing, said Australia has plenty of opportunity — and responsibility — in this space.

“Rare earths aren’t rare in Australia — especially light rare earths,” said Professor Valix.

“But water is one of the vulnerabilities.”

The bottleneck

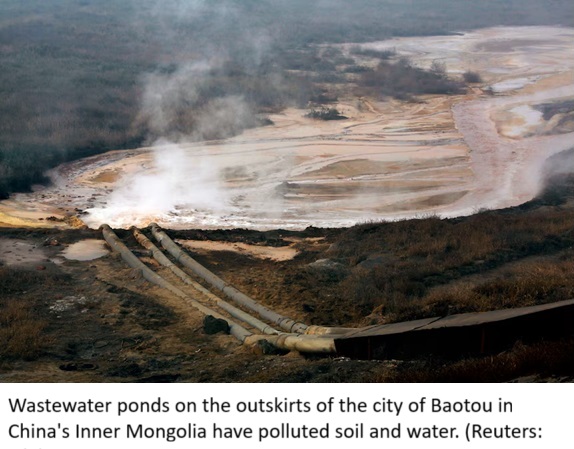

When researcher Jane Klinger first visited China’s Bayan Obo mine at Baotou in Inner Mongolia — the world’s largest rare-earth operation — more than a decade ago, she expected to see the future of green technology.

What she found instead was a cautionary tale: acidic wastewater and radioactive residue in unlined ponds along with contaminated rivers and farmland.

“The stuff we want is typically a very small percentage of what’s dug up,” Professor Klinger, author of Rare Earth Frontiers, told the ABC.

“And then there’s the waste that’s generated to separate the valuable bits from the rest of the rock.

“People don’t quite grasp how much waste we’re talking about.”

For every tonne of rare-earth oxide produced, roughly 2,000 tonnes of acidic wastewater are left behind.

It was a local taxi driver, pointing to a new hospital built to treat bone disorders, who tipped her off to what was unfolding around Baotou.

She discovered cases of cancers, arsenic poisoning and birth and joint deformities linked to years of unregulated dumping.

Australian National University professor of economic geology John Mavrogenes said the Chinese companies were mining by drilling and pouring chemicals into the holes.

“They found it was so bad environmentally that even China decided maybe they should quit,” he said.

The health and environmental impacts were so severe Beijing has since tightened regulations and cleaned up some sites.

It has also shifted much of its most-polluting refining methods to neighbouring Myanmar.

In Jiangxi province, China’s other main rare earth mining hub in the south, more than 100 mine sites have been shut down in the past decade and converted into parks, according to local media.

Learning from China’s mistakes

Experts insist Australia can do better.

The Donald Rare Earth and Mineral Sands mine in western Victoria — which was given major projects status last month — will use a method that uses fewer chemicals than hard-rock mining to extract rare earths.

Once operational, the site is expected to become the fourth-largest rare earth mine in the world outside China.

The company behind the project, Astron, plans to rehabilitate the land and send its rare-earth concentrate to Utah for further processing, where uranium will also be recovered.

Victoria bans uranium mining outright, but the US intends to use the by-product as fuel for nuclear power plants.

Professor Klinger said one of the most impactful lessons from what she found in China was simple.

“Don’t dump this stuff in tailings ponds without liners,” she said.

“Don’t contaminate groundwater, but also pay attention to ‘who’ is doing the modelling and monitoring.”

When the Donald mine starts production next year, processing is to take place in enclosed sheds, with waste sealed into containers and shipped off-site.

But Australia has not always had a spotless record: past projects such as fracking in the Northern Territory and old coal mines show how environmental oversight can fail.

The water dilemma

China dominates the separation and refining of rare earths, controlling over 90 per cent of global production.

In Western Australia, Iluka Resources is building Australia’s first rare earths refinery.

The process — crushing rock, separating minerals, and neutralising the waste — requires vast amounts of water.

Iluka’s refinery will consume just under 1 gigalitre of groundwater per year.

Iluka head of rare earths Dan McGrath told the ABC the refinery would operate as a zero liquid discharge facility.

“Our design avoids generating liquid waste altogether, and the reagents we use create a saleable fertiliser by-product instead of requiring disposal.

“All remaining solids will be disposed of in existing mine voids, removing the need for new waste containment facilities or above-ground disposal facilities.”

Professor Mavrogenes said water scarcity was already shaping where new mining projects could go ahead.

“Water is an issue because most ores are located in areas that don’t have enough water,” he said.

The Iluka refinery will produce both light and heavy rare earth oxides used in advanced manufacturing of items, including medical devices and defence weaponry.

A wastewater treatment plant will form part of the facilities, but the plan has drawn criticism amid ongoing water shortages.

In Victoria, Astron has secured water entitlement from Grampians Wimmera Mallee Water.

Geologists including Professor Mavrogenes have warned that a secure water supply and planning needed to account for climate change.

“Flooding can shut down processing, especially with heap leaching,” he pointed out.

Heap leaching is where a chemical solution is trickled through a heap of crushed ore, often in a pond, to dissolve the metals.

Other environmental concerns once shadowed Lynas Rare Earths, Australia’s largest producer of rare earths, which ships semi-processed concentrate to Malaysia for refining.

The company initially faced local protests over low-level radioactive waste.

Kuan Seng How, assistant professor in Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman’s Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, said Lynas had since built a permanent, sealed facility to prevent groundwater seepage — an expensive but necessary fix.

Together, Iluka’s new refinery and Lynas’ remediation effort illustrate the same lesson: refining is not just an engineering problem but a resource-management one.

A cleaner frontier

China now lines its wastewater ponds with bentonite clay to reduce leakage and collects some run-off for reuse.

Yet even those measures have not stopped some seepage leaking outward, according to a recent article published in the Chinese journal Modern Mining.

Industry and researchers are now exploring waterless extraction technologies such as solvolysis — a process that uses chemical solvents instead of water to extract rare earths.

“It can leach and separate the metals in one step,” Professor Valix said.

“But it hasn’t been scaled up yet — and right now it’s more expensive.”

She sees water management as the defining test of Australia’s ambitions.

Her colleague Susan Park from the University of Sydney added that as countries raced to upgrade rare earth processing, Australia must invest more in knowledge.

“One of the issues is the absence of long-term research and development into these technological processes and training people,” she said.

China may already be a step ahead, testing new techniques on a large scale.

In January, the Chinese Academy of Sciences claimed a breakthrough: an electrokinetic extraction technique that slashes the use of leaching agents by 80 per cent, mining time by 70 per cent and energy consumption by 60 per cent.

According to the scientists who revealed the development in the journal Nature Sustainability, the method could soon be viable for large-scale production.

For Australia, Professor Valix said the barrier was not capability but commitment.

“It’s not that we don’t have the technology,” she said.

“What we don’t have is the investment and the uptake market here like battery makers or manufacturers.”