HISTORY FELLOWSHIP WINNER TO EXPLORE HOW SOUTH AUSTRALIANS MOBILISED AGAINST URANIAM MINING IN THE ’70s

History Council of South Australia, 19 December 2025

Adelaide historian Dr Nicholas Herriot has been awarded the prestigious 2026 History Council of South Australia Fellowship for his project “Leave it in the Ground: South Australia, Uranium, and the Atomic Age”.

The project, which was the unanimous winner in a strong field of ten nominations, will investigate how South Australians mobilised against uranium mining and grappled with the promise and peril of the atomic age, focusing on the 1970s and early 1980s – a period of intense political controversy.

Dr Nicholas Herriot is an early career researcher specialising in Australian labour, environmental and social movement history. He teaches history at the University of Adelaide and serves on the executive of the Labour History Society (South Australia).

Supported by the State Library of South Australia, the $2000 History Council Fellowship is open to all Australians exploring South Australian history, and aims to foster research that deepens our understanding of the state’s past and its contributions to wider histories. The annual winner also receives 10 hours of library research support, library space and the use of a computer.

History Council of South Australia president Prof Matthew Fitzpatrick said the judges were impressed with Dr Herriot’s plan to explore the legacies of anti-nuclear campaigns in shaping contemporary debates about energy, sovereignty and environmental justice.

“The project is both topical and timely, resonating with current explorations into alternative energies and about the power of protest,” Prof Fitzpatrick said.

“By illuminating these aspects of our recent past, the research will help contextualise ongoing concerns about nuclear policy and environmental responsibility and highlight the library’s rich collections as vital resources for understanding the state’s unique identity.

Prof Fitzpatrick said the state library’s commitment to preserving and sharing the state’s documentary heritage contributed significantly to the success of the awards, and the advancement of historical research. He also thanked the Marsden Szwarcbord Foundation for its continued support.

State Library of South Australia director Megan Berghuis said she appreciated how Dr Herriot’s project would draw on the library’s extensive archival holdings, including oral histories, activist ephemera and rare periodicals.

Marsden Szwarcbord Foundation director Dr Susan Marsden AM said she was impressed by Dr Herriot’s intention to situate local activism within national and transnational networks.

Dutton’s nuclear revival smells rotten to Gens Y and Z

By Glenn Davies | 19 April 2025, https://independentaustralia.net/politics/politics-display/duttons-nuclear-revival-smells-rotten-to-gens-y-and-z,19640

Forty years on from the first Palm Sunday anti-nuclear marches, Peter Dutton’s attempt to revive nuclear power is thankfully still a hard sell, writes history editor Dr Glenn Davies.

THIS YEAR, Palm Sunday, the traditional day of protest for peace, will occur on 13 April.

Australia has a long history of resisting uranium mining and nuclear development. During the 1980s, Palm Sundays in Australia were occasions for enormous anti-nuclear rallies all across the country, reaching a peak in 1985.

On 19 June 2024, Peter Dutton announced:

“…nuclear energy for Australia is an idea whose time has come.”

At the same time, he released “the seven locations, located at a power station that has closed or is scheduled to close, where we propose to build zero-emissions nuclear power plants”.

Nothing announced by Peter Dutton today changes the fact that nuclear energy is, according to reams of expert analysis, economically unfeasible in Australia. This is as true today as it was in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Palm Sunday peace march is an annual ecumenical event that draws people from many faith backgrounds to march for nonviolent approaches to contentious public policies. The event is based on the account of Jesus’ procession into Jerusalem, which some see as an anti-imperial protest — a demonstration designed to mock the obscene pomp of the Roman Empire. Palm Sunday is now considered an opportunity to join together to demonstrate for peace and social justice.

A major focus of activism in Australia during the anti-nuclear movement in the 1980s was the campaign against uranium mining, as Australia holds the world’s largest reserves of this mineral.

The Australian anti-nuclear movement emerged in the late 1970s in opposition to uranium mining, nuclear proliferation, the presence of U.S. bases and French atomic testing in the Pacific.

During the 1980s, Palm Sundays in Australia saw enormous anti-nuclear rallies all across the country.

The annual Palm Sunday rallies were organised by the People for Nuclear Disarmament (PND), beginning in 1982 and reaching a peak in 1985.

On Palm Sunday in 1982, an estimated 100,000 Australians participated in anti-nuclear rallies in the nation’s biggest cities. In Melbourne, more than 40,000 people marched to call for nuclear disarmament and highlight the multiple dangers associated with uranium mining and nuclear power. They were joined by a similar sized rally in Sydney. During the same week 5000 marched in Brisbane while numerous other protests were held across Australia.

While 1984 was the year of George Orwell’s dystopian future, the 1980s were less about a surveillance society than nuclear fear. In 1984, Labor introduced the three-mine policy as a result of heavy pressure from anti-nuclear groups. This was also a time when many Australians were concerned that the secret defence bases at Pine Gap, North West Cape and Nurrungar, run jointly with the United States on Australian soil, were “high priority” nuclear targets.

An estimated 250,000 people took part in Palm Sunday peace marches in April and the Nuclear Disarmament Party gained seven per cent of the vote in the December 1984 Election and won a Senate seat. In addition, the election of the Lange Labor Party Government in New Zealand in July, resulted in New Zealand banning visits by ships that might be carrying nuclear weapons and were also considered targets in a nuclear war

The refusal of New Zealand to permit a visit by the USS Buchanan in February of that year threatened the future of the ANZUS alliance.

Australia did not follow the example of New Zealand.

In 1985, more than 350,000 people marched across Australia in Palm Sunday anti-nuclear rallies demanding an end to Australia’s uranium mining and exports, abolishing nuclear weapons and creating a nuclear-free zone across the Pacific region. The biggest rally was in Sydney, where 170,000 people brought the city to a standstill.

In 1985, I was a first-year James Cook University student living at University Hall. JCU students in Townsville supported the massive Palm Sunday rallies by our southern cousins in a public protest by tagging on the end of the May Day (Labour Day) march along The Strand.

As we marched behind the Townsville unionists with their hats and placards, remembering and publicly affirming the sacrifices their forebears had made – the mateship, the loyalty and the determination to build and protect the freedom and rights we now enjoy – we realised this march was about empowerment in a world where individuals still too often have little control over their own destiny when it comes to the workplace. And this was the lesson we young students learned on that day from our older working brothers, as we also were desperately looking for more say in the safety of our world.

May is a beautiful time of the year in Townsville, with breezy, high-skied blue days. Marching along The Strand, we were proclaiming our concerns for ensuring a better and safer world for all our futures.

It would be irresponsible for us not to chant:

Two, four, six, eight. We don’t want to radiate.

One, two, three, four. We don’t want no nuclear war.

By the late 1980s, the political, social and economic mood had swung firmly in favour of the anti-nuclear movement. Though it was clear that the three already functioning mines would not be shut down, the falling price of uranium, coupled with the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, ensured that there would not be a strong effort to broaden Australia’s nuclear program.

During the 1980s, there was a mushroom cloud shadow cast over Australia. The protests of the anti-nuclear movement were successful in linking the horror of nuclear war to the zeitgeist of the 1980s. The anti-nuclear movement served an important function in Australian politics, where it visibly prevented any further pro-nuclear policies from being enacted by the Australian Government.

Former Labor Environment Minister Peter Garrett is the lead singer of rock band Midnight Oil and a prominent nuclear disarmament activist since the 1980s.

He recently stated in a Sydney Morning Herald op-ed:

Younger voters understandably won’t know that a generation their age once packed the Sidney Myer Music Bowl with Midnight Oil, INXS and other friends to “Stop the Drop”.

They won’t remember our Nuclear Disarmament Party campaign, which won Senate seats in Western Australia and NSW in the ’80s.

They can’t know what it was like to grow up during the Cold War era or live through horrific meltdowns at the Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima nuclear power plants, which were also “completely safe” until the day that they weren’t.

But generations Y and Z can still smell a rotten idea when they give it a good sniff.

The use of nuclear energy as a solution to Australia’s future energy needs is still a hard sell.

Times have obviously changed since the 1970s, but significant political and economic barriers remain — and the problem of cost is still unsolved. This is compounded by apocalyptic visions of global destruction as part of our contemporary zeitgeist. It’s just that in its modern incarnation, the apocalypse has become more varied.

Gone is the single event; now we have a multiple-choice-question-sheet worth of ways to end our time on Earth. In the 2020s, the apocalypse continues to figure heavily in social life with constant references to wild weather, global financial crises, lone wolf terrorism, environmental collapse and zombie plagues.

And perhaps the greatest fear of all is that in this fracturing of fear may come complacency.

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton will continue to struggle to get traction, not only during the current Federal Election campaign but as long as the spirit of the 1985 Palm Sunday protest march lives.

Critical Archival Encounters and the Evolving Historiography of the Dismissal of the Whitlam Government (Part 6

By AIMN Editorial on January 12, 2025, By Jenny Hocking Continued from Part 5

The Lost Archive: Government House Guest Books

In 2010, I first requested access to the Government House guest books held by the Archives, which provide the details of visits and visitors to “their Excellencies” at Yarralumla. The catalogue lists a total of twenty-nine files, enumerated consecutively, constituting visitor books from May 1953 to February 1996. The guest books appear regularly from July 1961 until July 1974, before stopping altogether until December 1982.

The Archives insisted that the guest books for this period had never been transferred from Government House and they now appeared lost since neither institution claimed to hold them. What is puzzling in this regard is that Archives’ enumeration system, which numbers each file consecutively, has two consecutive numbers assigned yet not included in the catalogue corresponding to the missing dates, suggesting two missing files given identification numbers by the Archives which are no longer listed.

. The only other gap in these books, for a much shorter period between 1960 and 1961, has no such missing consecutive numbers in the catalogue which might accommodate a lost file…………………………………………………………………………………………

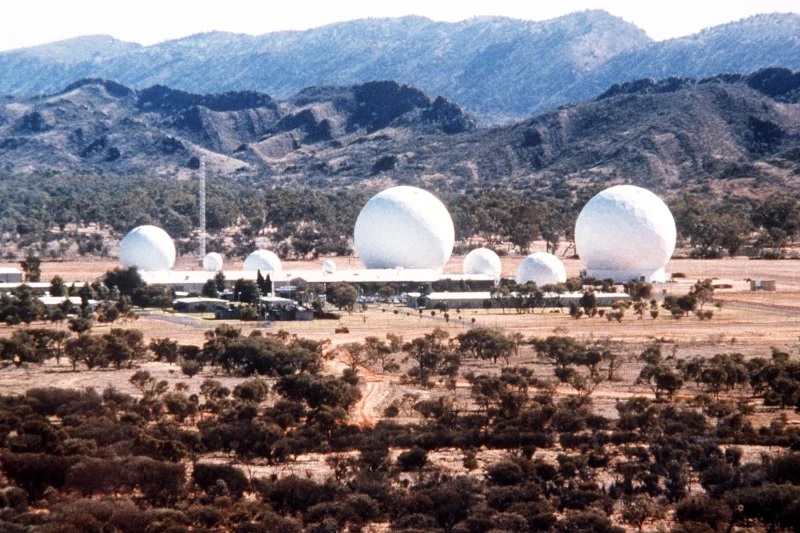

These missing guest books add fuel to the longstanding speculation that security and defence officials, notably the Chief Defence Scientist Dr John Farrands as the recognised authority on Pine Gap and the Joint Facilities, had briefed Kerr in the week before the dismissal about mounting security and defence concerns over Whitlam’s exposure of CIA agents working at Pine Gap, and his planned Prime Ministerial statement on this in the House of Representatives on the afternoon of 11 November 1975. …………………

The Burnt Archive: Sir John Kerr’s Prominent Supporters

In 1978, soon after Kerr left office, a cache of letters “of outstanding value” to Kerr was accidentally reduced to ashes in the Yarralumla incinerator……………….

Among his correspondents was the Queen’s second cousin, Lord Louis Mountbatten, Prince Philip’s uncle and King Charles III’s great mentor; the former Governor-General and distant royal relation, Viscount De L’Isle; and other prominent individuals supporting Kerr’s dismissal of Whitlam. These names alone indicate that these burnt letters were as important to history as they were to Kerr. …………..

…………… We now know, thanks to letters released in 2020 following the High Court’s decision in my legal action, that King Charles also fully supported Kerr’s actions…………………………..

Until their release in 2020 following the High Court’s decision in the Palace letters case they constituted the most significant “unattainable archive” in the dismissal panoply of secrets. The release of the letters signalled a rare moment of forced archival transparency in the face of determined refusals of access, and the harbinger of a significant historical re-evaluation of the dismissal in which they played a pivotal role.

What is critical for this discussion is that the closures of these otherwise public archives, both the Mountbatten papers and the Palace letters, were enabled by and remained hidden because of a claimed “convention” of Royal secrecy………………………………………………..

And so, this was how Kerr had labelled his letters to and from the Queen, as they had always been labelled, as “personal”. The only way to challenge the denial of access to personal records was to take a Federal Court action, a daunting and lengthy process. In 2016, with the support of a pro bono legal team, I commenced proceedings against the National Archives of Australia in the Federal Court, arguing that these Palace letters were not personal and should be publicly available, and seeking their release.

Four years and three court hearings later, the High Court found in a 6:1 decision that the Palace letters are not personal, leading to their release in full. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

A more complete history of the dismissal has emerged in fragments, still marred by partisan recollection, misplaced archives, and continuing secrecy. First, that Kerr was in secret contact with Fraser before he dismissed Whitlam; second, the definitive role of High Court justice Sir Anthony Mason, and finally, only in the last decade has the extent of royal involvement in Kerr’s decision become clear………………………………………….more https://theaimn.net/critical-archival-encounters-and-the-evolving-historiography-of-the-dismissal-of-the-whitlam-government-part

Critical Archival Encounters and the Evolving Historiography of the Dismissal of the Whitlam Government (Part 4)

COMMENT. This is heavy stuff.

I include it because it goes to explain how it came about that the USA pretty much owns Australia. USA has pretty much owned every Prime Minister since Whitlam.

Gough Whitlam had the guts to question the value of USA’s Pine Gap military intelligence hub.

So he paid the price for his courage

January 10, 2025 AIMN Editorial, By Jenny Hocking, Continued from Part 3

Kerr always claimed that the decision to dismiss the Whitlam government was his alone, that the leader of the opposition, Malcolm Fraser, did not know and that he had spoken to the High Court Chief Justice Sir Garfield Barwick only after he had reached his decision, and that the Palace was in no way involved. Sir Martin Charteris wrote on the Queen’s behalf to the Speaker, Gordon Scholes, soon after the dismissal; “The Queen has no part in the decisions which the Governor-General must take in accordance with the Constitution”.

This narrative of the Governor-General faced with an impossible decision and with no other option available but to dismiss the elected government, was well captured by the Sydney Morning Herald’s editorial the following day: “the course he [Kerr] has taken was the only course open to him”. In its recitation of Kerr’s statement of reasons, released within hours of the dismissal, the editorial makes no mention of the half-Senate election despite its pronouncement on whether other options were available to Kerr.

The invisibility of the half-Senate election is one of the notable features of much of the immediate commentary. Which is all the more puzzling since Whitlam was at Yarralumla on 11 November in order to call the half-Senate election, as Kerr well knew. Yet, in his statement of reasons, Kerr made scant reference to it and indeed misrepresented the half-Senate election in a way that then carried into much of the historical assessments to come………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Whitlam was due to announce the half-Senate election to the House of Representatives on the afternoon of 11 November 1975, and his signed letter to Kerr setting out the details for it was in his hand as he arrived in the Governor-General’s study. It can be found today among Kerr’s papers in the National Archives, with Kerr’s handwritten notation in the upper right corner: “the recommendation was not made”. The early histories of the dismissal were unaware of just how close Whitlam had been to calling the half-Senate election, some see it only as an option considered and not taken, while others fail to mention it at all.

………………………… The half-Senate election takes its place as a critical dismissal moment much overlooked by historical assessments, alongside the 1974 double dissolution election and the motion of no confidence in Malcolm Fraser two hours after his appointment as Prime Minister.

……………………………………………………. In a strident editorial rebuke “Sir John was wrong”, The Age alone among the immediate commentaries on Kerr’s precipitate action, which it termed his “Yarralumla coup d’etat”, implicitly invoked Hasluck’s response in 1974 of granting the election pending the passage of supply:

We are not convinced the decision he [Kerr] took was the only one open to him, or that it was necessary to take it now […] we should like to know if Sir John considered the possibility of urging Mr. Fraser to allow the Senate to pass interim Supply so that a half-Senate election could be held.

Central to the narrative of lonely inevitability, Fraser and Kerr repeatedly denied having any prior contact or warning before the dismissal,

…………………… after a decade of denial Fraser admitted his prior knowledge of the dismissal and his agreement on the terms of his appointment with Kerr. …………………..

………………………………………………………………………………It is an understatement to say that this shared agreement between the Governor-General and the soon to be appointed Prime Minister lacking the confidence of the House, regarding a policy decision directly affecting the Governor-General himself, raises serious political, ethical, and constitutional issues………………………………………………………. more https://theaimn.net/critical-archival-encounters-and-the-evolving-historiography-of-the-dismissal-of-the-whitlam-government-part-4/

Critical Archival Encounters and the Evolving Historiography of the Dismissal of the Whitlam Government (Part 2)

I will never forget the day when I, living in a country area, ran to answer a phone call. It was my mother, in the faraway city. And I’ll never forget her exact words: “The queen’s man has sacked our elected Prime Minister!”

My Mum summed it up. Later, I have realised that this was a case of the UK government toeing the line of the USA government, and making sure that Australia got that USA military intelligence hub, Pine Gap.

January 8, 2025 AIMN Editorial, By Jenny Hocking

Continued from Part 1

After years of legal action, still absent from public view are crucial documents from a most contentious time in British imperial history: the 1947 and 1948 diaries covering the Mountbattens’ shared involvements in pre-Independence India, transition and partition, among “scores of other files” not yet released.

These remain locked away, and Lownie has spent £250,000 of his own funds in pursuit of public access to papers which constituted a purportedly public archive, while the Cabinet office has spent £180,000 keeping them secret. Particularly disquieting is Lownie’s recent claims that he has himself become the target of security surveillance as he continues to pursue the closed Mountbatten files.

Somewhere among those voluminous Mountbatten papers are letters between Mountbatten and the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, about the dismissal of the Whitlam government. These letters were briefly cited by Mountbatten’s authorised biographer Philip Ziegler in which Mountbatten declared that he “much admired” Kerr’s “courageous and constitutionally correct” action in dismissing Gough Whitlam.

Several years ago, I visited Southampton University hoping to see Mountbatten’s dismissal correspondence with Kerr since, as discussed below, bizarre circumstance means that it no longer exists in Kerr’s papers in the National Archives of Australia. Although Ziegler had been granted access and had quoted from Mountbatten’s congratulatory letter to Kerr, I was denied access to the diaries and letters. Instead, I was handed some thin, rather desultory files containing a handful of itineraries, dinner placements, menus, and invitations to Mountbatten during his visit to Australia. No diaries and certainly no letters between Mountbatten and Kerr.

……………………………In relation to Kerr’s secret correspondence with the Queen, “the Palace letters” regarding the dismissal, it was the use of this uniquely powerful word in the archival lexicon – “personal” – that had placed the letters outside the reach of the Archives Act 1983 and necessitated an arduous Federal Court action to challenge their continued closure. Livsey notes in relation to the migrated Kenyan archive that the construction of “regimes of secrecy” in which the label “personal” was used to control access to and knowledge of British colonial practice; “files labelled ‘Personal’ could be consulted by white British officials only and ‘should not be sighted by local eyes’”…………………..

Lownie’s now four-year legal battle has been described as eerily similar to the Palace letters legal action which I took against the National Archives of Australia in 2016, arguing that the Queen’s correspondence with the Governor-General was not personal, and seeking its release. The case ended in the High Court in 2020 with a resounding 6:1 decision in my favour, the Court ruling that the Palace letters are, as I had argued, not personal and that they are Commonwealth records and come under the open access provisions of the Archives Act. The letters were released in full in July 2020, in a striking rebuff to the claimed convention of royal secrecy on which the Archives had in part relied.

…………………………………….. At its most significant, the denial of access to royal documents as “personal” enables the sophistry that the monarch remains politically neutral at all times to persist……………….

…………Although the Queen was publicly a careful adherent of that core requirement of neutrality, something the “meddling Prince” Charles most assertively was and is not, Hocking argues that “the much vaunted political neutrality is a myth, enabled and perpetuated by secrecy”. Professor Anne Twomey similarly notes that “If neutrality can only be maintained by secrecy, this implies that it does not, in fact, exist”.

Our own history gives us a powerful example of the way in which archival secrecy functions as a Royal protector, casting a veil over breaches of the claimed political neutrality of the Crown, in the changing historiography of the dismissal of the Whitlam government. ……………………….

For decades, the dismissal history was constrained by the impenetrable barrier of “Royal secrecy” which denied us access firstly, to any of Kerr’s correspondence with the Queen, ………………………………………….

Sir John Kerr’s abrupt dismissal, without warning, of the Whitlam government on 11 November 1975 just as Whitlam was to call a half-Senate election, was an unprecedented use of the Governor-General’s reserve powers and “one of the most controversial and tumultuous events in the modern history of the nation”, as the Federal Court described it.

These powers, derived from those of an autocratic Monarch untroubled by parliamentary sovereignty and even less by the electoral expression of the popular will, had not been used in England for nearly two hundred years, and never in Australia…………………………………………………………………. more https://theaimn.net/critical-archival-encounters-and-the-evolving-historiography-of-the-dismissal-of-the-whitlam-government-part-2/

Jenny Hocking is emeritus professor at Monash University, Distinguished Whitlam Fellow at the Whitlam Institute at Western Sydney University and award-winning biographer of Gough Whitlam. Her latest book is The Palace Letters: The Queen, the governor-general, and the plot to dismiss Gough Whitlam. You can follow Jenny on X @palaceletters.

The dirty history of ‘Nukey Poo’, the reactor that soiled the Antarctic.

By Nick O’Malley, July 10, 2024 , https://www.theage.com.au/environment/conservation/the-dirty-history-of-nukey-poo-the-reactor-that-soiled-the-antarctic-20240708-p5jrzd.html

The rekindled nuclear debate in Australia has stirred old memories in some of a little-known chapter of our region’s history, when the US Navy quietly installed what today we might call a small modular reactor at the US Antarctic base on Ross Island.

The machine, nicknamed “Nukey Poo” by the technicians who looked after it, was installed at McMurdo base in 1961, when Antarctic exploration was expanding and nuclear energy had developed a bright futuristic sheen.

Things did not end well.

Back then, as now, Antarctic missions relied upon lifelines with distant homes. Supplies had to be carried long and sometimes dangerous distances. The US kept its Antarctic sites supplied via an ongoing supply mission called Operation Deep Freeze, which was based at the McMurdo Naval Air Facility.

According to an article on the Nukey Poo incident published in 1978 by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists – a journal concerned with the potential danger of nuclear technology, founded by Albert Einstein and veterans of the Manhattan Project – while a gallon of diesel cost the US Navy US12¢ back then, by the time the Americans shipped supplies to McMurdo, diesel cost 40¢ a gallon. At South Pole station, diesel was worth $12 a gallon.

But the then US Atomic Energy Commission had a solution to save costs on transporting supplies. What if McMurdo, and other distant US bases, were supplied by small transportable nuclear reactors? Congress agreed and soon the Martin Marietta Corporation won a contract to build them.

In an advertisement in Scientific American, the company boasted in language reminiscent of today’s debate over modular reactors that “because nuclear energy packs great power in little space, it’s extremely useful when you need electricity in remotes spots. It’s portable and gives you power that last for years …” Soon, the company said, nuclear power might be carrying us to outer space and frying our eggs.

A reactor named PM-3A (PM stood for “portable, medium powered”) was shipped out in sea crates and installed at McMurdo – which is within New Zealand-claimed Antarctic territory – over the summer of 1961 and became known on the base as Nukey Poo. Because cement would not cure in the frigid climate, the reactor was not encased in concrete, rather its four major components sat in steel tanks embedded in gravel and wrapped in a lead shield.

Admiral George Dufek described the moment as “a dramatic new era in man’s conquest of the remotest continent”. The US administration was certain the reactor did not violate the Antarctic Treaty’s declaration that “any nuclear explosions in Antarctica and the disposal there of radioactive waste material shall be prohibited”.

Within a year, Nukey Poo caused its first fuss, a hydrogen fire in a containment tank that led to a shutdown and energy shortages. Icebreakers fought to break through and fuel for generators was delivered by helicopter, which burned as much as they delivered over the course of a flight. Over the following years, Nukey Poo proved so unreliable and expensive to maintain that the military gave up hopes of using the technology to displace diesel at other remote locations.

In 1972, the navy began the three-year task of decommissioning the reactor and decontaminating the site. During that process, they discovered corrosion that technicians feared may have caused leaks of irradiated material. No detailed investigation was done. The secretary of the US National Academy of Sciences said the program was ended due to a series of malfunctions and the possibility of leaks, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists reported. The New Zealand government declared the decision was economic.

Either way, it was decided not only to remove the reactor, but half the hillside it was built into. Eventually 12,000 tonnes of irradiated gravel and soil was removed on supply ships to be buried in concrete lined pits in the United States.

The young Australian scientist, Dr Howard Dengate, who had run one of the NZ bases, hitched a lift on one those ships, the Schuyler Otis Bland, in 1977. Dengate recalls a grumpy captain who once swore at him for inviting bad luck on the ship by whistling on deck. The captain, Dengate recalled this week, blamed him for “whistling up” the storm that struck the vessel before the Australian disembarked in New Zealand and the ship sailed on to the US.

Though the reactor was little discussed in the wider world, no secret was made on the base of the reactor or its impact. Indeed, Dengate recalled finding an operating manual for the reactor in the American rubbish pits that New Zealanders had developed the habit of fossicking in.

But the story did not end there.

In 2011, an investigation by journalists of News 5 Cleveland found evidence that McMurdo personnel were exposed to long-term radiation, and in 2017 compensation was paid to some American veterans of the base. A year later, New Zealand officials announced that it was possible that New Zealand staff were also affected.

It has since been reported that four New Zealanders had raised claims about their ill health since their time in the Antarctic.

In 2020, the Waitangi Tribunal, a permanent commission in New Zealand to investigate cases against the Crown, launched inquiries. They are not yet complete.

Asked if he was concerned about travelling with the irradiated material, Dengate said he was not. “We were young and dumb and adventurous,” he told this masthead of his time in the Antarctic.

Best we Forget – Australia’s 70 year old nuclear contamination secrets about to be exposed

by Sue Rabbitt Roff | Jun 28, 2024 https://michaelwest.com.au/best-we-forget-australias-70-year-old-nuclear-contamination-secrets-about-to-be-exposed/?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_term=2024-07-04&utm_campaign=Michael+West+Media+Weekly+Update

While Peter Dutton gets headlines for his nuclear fairytale and the Labor Government presses on with its AUKUS submarines, the fallout from nuclear bomb testing in the Pilbara in 1956 finally reaches court. Sue Roff reports from London.

In 1956, on the remote Montebello Islands off Western Australia, an atomic bomb was tested. It was supposed to be no more than 50 kilotons, but in fact measured 98 kilotons, or more than six times the strength of the bomb dropped over Hiroshima in 1945.

Ever since then, Australian and UK Governments have suppressed the facts and denied compensation to the victims. That may finally be about to change.

Three months ago, veterans of Britain’s Cold War radioactive weapons tests formally launched proceedings against the UK Ministry of Defence, alleging negligence in its duty of care to the men themselves and their families before, during and after the tests that began at the Montebellos in 1952.

MWM, “The opening phase seeks the full disclosure by the Ministry of Defence of all records of blood and urine testing conducted during the weapons trials, with compensation sought for MoD negligence and recklessness if they were lost or destroyed.”

At the same time, the veterans have made an offer to resolve their claim through the creation of a Special Tribunal with statutory powers to investigate and compensate if decades of cover-up are established.

A very big bomb

In October 1955, the Director of British atomic and thermonuclear tests in Australia, Professor William Penney, wrote to the Chair of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority about the two detonations that were planned for the Montebello Islands in May and June 1956:

‘Yesterday I think I gave you the impression that the second shot at Montebello will be about 80 K.T. [kilotons]. This is the figure to which we are working as far as health and safety are concerned. We do not know exactly what the yield is going to be because the assembly is very different from anything we have tried before.

We expect that yield will be 40 or 50, but it might just go up to 80 which is the safe upper limit.

In fact, in recent years, it has been listed on the website of ARPANSA [the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency] as 98 kilotons.

The politics

A UK memo found in the UK National Archives that is undated but filed around August 1955, states:

“TESTS IN Montebello ISLANDS (CODE NAME ‘MOSAIC’) 25 7.

“We had agreed with the Australian Government that we would not test thermo-nuclear weapons in Australia, but [Australian Prime Minister] Mr. Menzies has nevertheless agreed to the firings taking place in the Montebello Islands (off the North-West coast of Western Australia), which have already been used before for atomic tests [emphasis added].”“As already explained, the Australians are very sensitive on the question of thermo-nuclear explosions, and although the true character of these tests is understood by the authorities immediately concerned, knowledge of the trials is restricted to a very small circle and no public statement has so far been made; when it is made, it will therefore require very careful handling.”

“Apparently it is still being very carefully handled by government agencies. 70 years after the British atomic and thermonuclear tests started in Australia scores of files held in the Australian National National Archives are marked ‘Not yet examined’. We urgently need to create an independent archive of Australia’s nuclear past.”

The falloutIn Roeboure, some 200km away from the blast, a witness – then seven-year-old John Weiland wrote later of “hearing and feeling the blast before going outside to see the cloud. My mother said she remembers material falling on her. I was in primary school at the time and we all stood out on the verandah to watch the cloud.”

Weiland later wrote to ARPANSA asking “if any testing was done or any follow up done particularly with the 30 or so children of the school. But I was told there was no radiation blown across from the islands.”

In December 1957, eighteen months after the second G2 Operation Mosaic blast at the Montebellos, the five scientific members of the Atomic Weapons Safety Committee (AWSC) appointed by the Australian government published a report titled ‘Radioactive Fallout in Australia from Operation ‘Mosaic’ in The Australian Journal of Science.

without approaching the mainland of Australia.’ However ‘a pronounced stable layer produced a marked bulge on the stem which trapped a small quantity of particulate material and this was spread to the south-east of the Montebello Islands …The more finely suspended material’ or ‘debris’ was dispersed in the first 48 hours …’ although there was light rain over Marble Bar.

Thirty years after this AWSC report, the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia issued its 1987 report after 18 months of hearings around Australia and in London. In relation to Mosaic G2 it reported:“7.4.25 The post-firing winds behaved similarly to those after Gl, i.e. they weakened and then began to blow to the south and east. An analysis of the trajectories of fallout particles showed that fallout at Port Hedland occurred 24 hours after the explosion and consisted of particles that originated from 20,000 feet in the region of the top of the stem and the bottom of the cloud….[RC 270, T24/57).”

“Clearly part of the main cloud did cross the mainland.”

The Royal Commission also concluded, “The Safety Committee communications with the Minister for Supply soon after the second explosion, when it reported that the cloud had not crossed the coast, with the implication that there was no fallout on the mainland, were misleading.”

Nearly forty years later, in January 2024, John Weiland submitted a query to the Talk to A Scientist portal of ARPANSA, asking for information. The unsigned response four days later referred him to Appendices B & C of a 32 year old document attached to the official response. A report, ‘Public Health Impact of Fallout from British Nuclear Tests in Australia, 1952-57, has a diagram annotated ‘Trajectories taken by radioactive clouds across Australia for the nuclear tests in the Mosaic and Antler Series. The main debris clouds from Mosaic Rounds 1 and 2 are not shown as they remained largely over the Indian Ocean, moving to the northeast parallel to the coast.’ (emphasis added).This diagram [ on original) doesn’t correlate with the maps in the Royal Commission Report north of Broome nor those of the AWTSC report in 1957 south of Port Hedland.

I have published extensive archival evidence about the score of coverups that have occurred over the past 70 years.The cover-up

They range from the agreement of Prime Minister Menzies to the progressive testing of hydrogen/thermonuclear devices in preparation for the full assembly in 1957 for the Grapple tests at Christmas Island, including testing less than two months before the start of the 1956 Olympic Games in downwind Melbourne, and Menzies’ hope of getting tactical nuclear weapons for Australia by his collusion.

They also include the submission of ‘sanitised’ health data on Australian test participants to the 1985 Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia.I presented my concerns about the role of UK official histories of the tests in a seminar hosted by the Official Historian of the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office by invitation in February 2024.

Representing the victims, Oli Troen adds that “The Veterans previously sought redress through the English Courts, losing in the Supreme Court in 2012 when they could not prove they experienced dosages of radiation exposure. This meant they could not demonstrate their injuries resulted from that exposure.”

Blood tests taken at the time and in the years after presence at a test site are key to proving whether the legacy of rare illnesses, cancer and birth defects reported by the veterans is due to radiation from the nuclear tests and whether the government is culpable and can now be held accountable for their suffering.

A Freedom of Information tribunal has ordered the handing over of the blood tests of veteran and decorated hero Squadron Leader Terry Gledhill, who led ‘sniff planes’ into the mushroom clouds of thermonuclear weapons on sampling missions. This new case seeks to force the government to hand over such records for up to 22,000 UK veterans.

US bases including Pine Gap saw Australia put on nuclear alert, but no-one told Gough Whitlam

“The Australian government takes the attitude that there should not be foreign military bases, stations, installations in Australia. We honour agreements covering existing stations. We do not favour the extension or prolongation of any of those existing ones.” – Gough Whitlam

ABC News, By Alex Barwick for the Expanse podcast Spies in the Outback, 25 Apr 24

During the 1972 election campaign, Gough Whitlam promised to uncover and share Pine Gap’s secrets with Australians.(ABC Archives/Nautilus Institute)

When Australia was placed on nuclear alert by the United States government in October 1973, there was one major problem.

No-one had told prime minister Gough Whitlam.

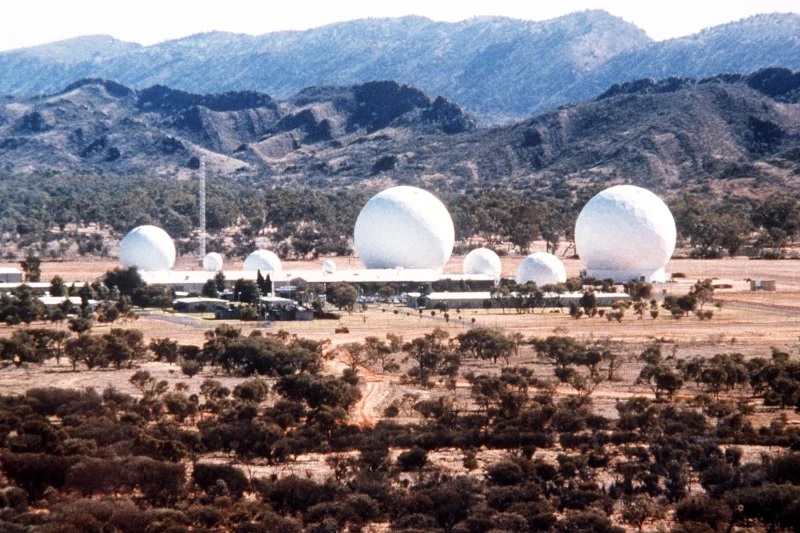

One of the locations placed on “red alert” was the secretive Pine Gap facility on the fringes of Alice Springs.

Officially called a “joint space research facility” until 1988, the intelligence facility was in the crosshairs with a handful of other US bases and installations around Australia.

In fact, almost all United States bases around the world were placed on alert as conflict escalated in the Middle East. Whitlam wasn’t the only leader left out of the loop.

A prime minister in the dark

“Whitlam got upset that he hadn’t been told in advance,” Brian Toohey, journalist and former Labor staffer to Whitlam’s defence minister Lance Barnard, said.

Toohey said Whitlam should have been told that facilities including North West Cape base in Western Australia, and Pine Gap were being put on “red alert”.

“There had been a new agreement knocked out by Australian officials with their American counterparts, that Australia would be given advance warning.”

They weren’t.

Suddenly, the world was on the brink of nuclear war.

Why were parts of Australia on ‘red alert’?

The Cold War superpowers backed opposing sides in the Yom Kippur War.

The Soviet Union supported Egypt and the United States was behind Israel.

As the proxy war escalated in October 1973, United States secretary of state Henry Kissinger believed the crisis could go nuclear and issued a DefCon 3 alert.

A DefCon 3 alert saw immediate preparations to ensure the United States could mobilise in 15 minutes to deliver a nuclear strike.

The aim was to deter a nuclear strike by the Soviets.

And, it simultaneously alerted all US bases including facilities in Australia that a nuclear threat was real.

This level of alert has only occurred a few times, including immediately after the September 11 attacks.

Politics, pressure and protest

The secretive intelligence facility in outback Australia caused Whitlam more trouble beyond the red alert.

During the 1972 election campaign, the progressive politician had promised to lift the lid on Pine Gap and share its secrets with all Australians.

“He gave a promise that he would tell the Australian public a lot more about what Pine Gap did,” Toohey said.

But according to Toohey, the initial briefing provided to Whitlam and Barnard by defence chief Arthur Tange left the prime minister with little to say.

“Tange came along and he said basically that there was nothing they could be allowed to say. And that was just ridiculous,” Toohey said.

“He said, the one thing he could tell them was the bases could not be used in any way to participate in a war. Well, of course they do.”

Whitlam would cause alarm in Washington when he refused to commit to extending Pine Gap’s future.

In 1974 on the floor of parliament he said:

“The Australian government takes the attitude that there should not be foreign military bases, stations, installations in Australia. We honour agreements covering existing stations. We do not favour the extension or prolongation of any of those existing ones.”

According to Toohey, “the Americans were incredibly alarmed about that”.

“As contingency planning, the whole of the US Defence Department said that they would shift it to Guam, a Pacific island that America owned,” he said.

And the following year, allegations would emerge that the CIA were involved in the prime minister’s dismissal on November 11, 1975…………… https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-04-24/when-australia-was-put-on-nuclear-alert-expanse-podcast/103733194

Australia has had many significant inquiries into nuclear power, over the past 60 years

Paul Richards, 6 Mar 24

Peter Dutton and his Coalition opposition party keep calling for a “mature” debate on nuclear power, as if no-one has ever discussed it seriously. But Australia has had many “mature” inquiries and discussions related to nuclear energy, uranium mining, and the nuclear fuel cycle over the past 60 years. Here are some notable ones:

1.] Radium Hill Royal Commission (1953):

This inquiry examined the safety and health concerns related to uranium mining at Radium Hill in South Australia. It investigated radiation exposure for workers and nearby communities and made recommendations for improved safety measures.

2.] McMahon Report (1955):

Commissioned by the Australian government, this report explored the potential for nuclear power generation in Australia. It assessed the feasibility, costs, and benefits of establishing nuclear power plants and considered the country’s uranium resources.

3.] Fox Report (1976):

The report, officially titled “Uranium Mining, Processing, and Radiation Safety”, was commissioned by the Australian government to investigate the health and safety aspects of uranium mining and processing. It examined radiation exposure risks for workers and surrounding communities and recommended regulatory measures.

4.] Joint Select Committee on the Environment (1980-1981):

This parliamentary committee inquired into the environmental and health impacts of uranium mining and processing in Australia. It examined issues such as radiation contamination, waste management, and rehabilitation of mining sites.

5.] Commonwealth Government Inquiry into Nuclear Energy (2006):

This inquiry examined the potential for Australia’s involvement in the nuclear fuel cycle, including uranium mining, nuclear power generation, and waste management. The resulting report, known as the Switkowski Report, provided analysis and recommendations on these issues.

6.] South Australian Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission (2015-2016):

This inquiry was established by the Government of South Australia to investigate the potential for the state’s further involvement in the nuclear fuel cycle, including uranium mining, enrichment, energy generation, and waste management. The final report provided a comprehensive analysis and recommendations regarding these issues.

7.] Federal Government Inquiry into Nuclear Energy (2019):

The Australian Federal Parliament’s Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy conducted an inquiry into the prerequisites for nuclear energy in Australia. It examined the economic, environmental, and safety implications of nuclear power generation and assessed public opinion and regulatory frameworks.

These inquiries reflect Australia’s ongoing evaluations and debates surrounding nuclear energy, uranium mining, and the broader nuclear fuel cycle, considering various economic, environmental, social, and political factors over the past 60 years.

The case of Yaroslav Hunka, and its echoes in Australia’s history

Jayne Persian 9 Oct 23 https://overland.org.au/2023/10/the-case-of-yaroslav-hunka-and-its-echoes-in-australias-history/?fbclid=IwAR3fq-DqIxk7y61nKGzy77tlYkYp9vU9JaywMHQdzsQEcC6nrbU5dzrIrFk

Dr Jayne Persian is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Southern Queensland and the author of Fascists in Exile: Post-War Displaced Persons in Australia, forthcoming with Routledge Studies in Fascism and the Far Right.

On 22 September, during a visit to the Canadian Parliament by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Speaker Anthony Rota publicly introduced ninety-eight-year-old Yaroslav Hunka as a constituent ‘who fought for Ukrainian independence against the Russians’ as part of the First Ukrainian Division during the Second World War. He was ‘a Ukrainian hero, a Canadian hero, and we thank him for all his service.’ Hunka received a standing ovation from all present.

This scene was reported two days later by an antifascist site on Twitter, who pointed out that the First Ukrainian Division was also known as the Waffen-SS Galizien Division. Canadian academic Ivan Katchanovski linked to a veterans’ webpage in which Hunka wrote that he had been a volunteer recruit to the Galizien Division in 1943. Hunka had also uploaded photographs showing him in uniform with the ‘boys’.

The Kremlin immediately reacted, with spokesman Dmitry Peskov arguing that ‘such sloppiness of memory is outrageous.’ Opposition Leader, Pierre Poilevre, described this incident as the worst diplomatic embarrassment in Canada’s history. Rota resigned, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was forced to apologise unreservedly.

These embarrassing episodes continue to occur in countries that resettled the post-war displaced persons of Central and Eastern Europe. This mass of around one million people had refused to return to homes that were under Soviet control. As well as concentration camp inmates and forced labourers, these political refugees included soldiers who had fought in German military units, as well as civilian collaborators. Security screening was difficult and there was also some sympathy from the Allied military authorities for veterans on the losing side. Whole cohorts were resettled in Britain, including 8,000 Ukrainian members of the Waffen-SS Galizien Division. Ukrainian nationalist declarations were also treated seriously. While all Ukrainian displaced persons held either Polish or Soviet Union citizenship, they were treated as a separate group quite quickly.

Many of these men should have been charged with war crimes. The German-led Holocaust had relied on the firepower and administrative skill of non-German Central and Eastern Europeans, including Ukrainians. Ukrainian anti-Soviet and anti-Polish nationalists were initially involved in individual and group paramilitary acts, including voluntary local pogroms and/or acts of murder before or beside the German occupation. One of the pogroms, which involved the massacre of 12,000 Jews, was named Aktion Petliura after the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura, who had been assassinated by a Ukrainian Jew (this assassination itself framed as retaliation for earlier pogroms) in 1926.

After the initial wave of pogroms, Ukrainians became progressively involved with an institutionalised German genocidal machinery. Ukrainians joined a Ukrainian Auxiliary Police Force (Schutzmannschaft), the German security police (Sicherheitspolizei, SiPo) and the intelligence agency (Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers-SS, SD). Others hunted Jews in their forest warden jobs. Local policemen were empowered to kill anyone the Germans defined as enemies of the state, including Jews; indeed, the Germans relied on the dramatically increased numbers of local forces to do the dirty work of the Holocaust, including the shooting of children. Between 1941 and 1944, 1.6 million Jews had been murdered in Ukraine. In 1943, 100,000 of these men volunteered to join the Waffen-SS Galizien Division. In this capacity, they have been accused of murdering Polish civilians.

The United Nations’ International Refugee Organisation resettled the displaced persons in the United States, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. The western world was eager to use the labour of these healthy, white, and stridently anti-communistic young men. Australia resettled 170,700 displaced persons including Poles, ‘Balts’ (Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians), Yugoslavs, Ukrainians and Hungarians. There was immediate criticism by Jewish groups and sections of the press that the new migrants included war criminals but these were roundly dismissed as Soviet communist propaganda.

Decades later, all four of the main resettlement countries instituted judicial processes against the alleged perpetrators of the Holocaust who were now resident in their countries. In Australia, such men were guaranteed a fair criminal trial: the evidence, for crimes that occurred over forty-five years before, had to include documentary and material evidence and, ideally, eyewitnesses to the alleged individual perpetrator carrying out a war crime. Of course, the nature of the Holocaust was such that very few eyewitnesses to genocide survived in order to testify against individual killers.

After a flawed investigative process, only three men were charged. All three were Ukrainians who had resettled in Adelaide. Ukrainian auxiliary policeman Mikolay Berezowsky was accused of being party to a mass murder of 102 Jewish villagers. Henry Wagner, an ethnic German liaison officer between the German and Ukranian auxiliary police force, was charged with being party to two mass murders, including the shooting of nineteen part-Jewish children. Forest warden Ivan Polyukhovich was accused of hunting and killing Jews under the German occupation, and in taking part in a mass shooting. However, the evidence bar was so high that there were no convictions.

Immediately after the unsuccessful war crimes trials, Ukrainians again attracted attention with an award-winning novel by Helen Demidenko, purporting to be written by a Ukrainian-Australian and based on the life story a member of that community. To the great embarrassment of the Australian literati, Demidenko was soon unmasked as English-Australian Helen Darville, who had attended the Polyukhovich trial with a young man who was noticed to be repeatedly muttering ‘Jews’.

Many responses to Ivan Katchanovski’s tweets shedding light on this unsavoury history — one that Canada and Australia share — claimed that this was not the time to be critiquing Ukraine or Ukrainian nationalists. Ukraine was, of course, invaded by Russia in 2022 and that war is ongoing. Most in the West sympathise with, and support, Ukraine’s fight. And Russia has attempted to smear all Ukrainians with accusations of Nazism, which is simply not true. Dismissing inconvenient histories and the problematic pasts of individual migrants to both Canada and Australia, however, is not useful.

The complicity of the West in assisting perpetrators to escape justice should be acknowledged, and we must be wary of any attempt to normalise fascist views and actions in the public sphere.

Why Nazis still call Australia home

June 6, 2001, Issue 451 https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/why-nazis-still-call-australia-home?fbclid=IwAR0c5JRnrDTxKQy88O6uDOuhIYDPdjsDwn-Dh-sK-4L41HQ3uvHE_mJ_on8

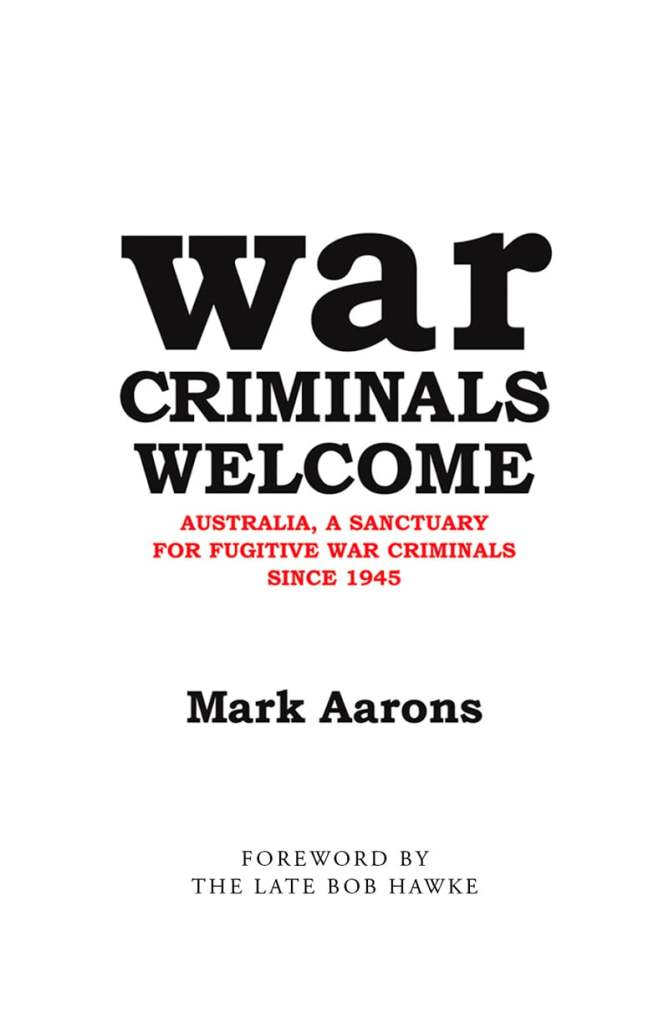

War Criminals Welcome: Australia, A Sanctuary for War Criminals since 1945

By Mark Aarons

Black Inc, 2001

649 pp, $34.95 (pb)

When justice minister Amanda Vanstone said that the alleged Latvian war criminal Konrads Kalejs was “welcome” to stay in Australia, it was a revealing slip of the tongue. Since 1947, when the first Nazi war criminals arrived in Australia, “successive governments have knowingly allowed hundreds of men responsible for the cruel imprisonment, torture, rape and mass execution of tens of thousands of innocent civilians to make Australia home”. This is the damning conclusion of Mark Aarons’ book on how and why Labor and Liberal governments have allowed Nazi killers into Australia and protected them.

When the first European refugees arrived in Australia after the second world war, under the displaced persons migration scheme, their number included dozens of fascist collaborators from central and eastern Europe. Amongst them were officers, like Kalejs, of the Arajs Kommando, the Nazi-controlled Latvian security police, a volunteer police auxiliary which, by mass shootings, mobile gas vans or deportation to concentration camps, wiped out Latvia’s 70,000 Jews and murdered other racial, religious and political targets of the Nazis.

There were also Croatian fascists, whose cruelty is said to have sickened even hardened German Nazis. One of them was Srecko Rover, alleged to be the fanatical officer in charge of a mobile killing unit which massacred Jews, Serbs and, especially, communist-led partisans in the Balkans. Recruited by US intelligence before arriving in Australia in 1950, Rover immediately began a decades-long career as an ASIO agent and organiser of terrorist operations against left-wing migrants and President Josep Bros Tito’s communist Yugoslav government.

How did these killers slip through the screening process which was supposed to weed out war criminals from genuine refugees? Post-war confusion, incompetence, diffidence and corruption by Allied immigration officials in Europe were partly to blame. But more important was the Cold War political climate.

Many anti-socialist conservatives thought the Allies had fought the wrong war (it should have been with Hitler against Stalin). Australia’s attorney-general Bob Menzies in the 1930s was an admirer of the Nazi state as a bulwark against “atheistic Bolshevism”. The Nazi war criminals may have been anti-Semitic mass murderers but they were anti-communists and therefore welcome.

These Nazis found a ready champion in ASIO. Allied intelligence agencies gave the Nazis a clean bill of health in the screening process, allowing them to assume false identities or lie about their past, and frequently recruiting them as agents. ASIO put them to use as spies and covert operatives against the migrant left.

When Australian governments were forced to investigate suspected war criminals, they happily relied on ASIO which was far more interested in putting Nazis on the payroll than investigating their crimes. When the Yugoslav government requested the extradition of Milorad Lukic and Mihailo Rajkovic in 1951 for their fascist war crimes at POW camps, the head of ASIO in Western Australia reported that the two men, ardent anti-communists and supporters of Menzies, “represent a body of Yugoslavs who cause infinitely less trouble to this organisation than the great body of their fellow immigrants”, as well as providing “invaluable assistance to ASIO”, as ASIO boss Charles Spry wrote to the head of the Commonwealth Department of External Affairs.

Post-war Labor and Liberal governments ignored mounting evidence of Nazi arrivals. Refugees, immigration staff, crew members of US Army transport ships and even ASIO’s predecessor, the Commonwealth Investigation Service, reported anti-Semitic incidents, including serious assaults, on the refugee ships and in the migrant reception camps and hostels. The blood group tattoos, or scars from their removal, observed under the left armpit were a giveaway of SS membership. Nazi memorabilia, such as Hitler statues and swastikas, were regularly seized in the migrant camps.

When the import of Nazis turned to the so-called Volkdeutsche, ethnic Germans expelled from Stalinist Europe under the terms of the post-war settlement, many brought with them not only trade skills for major infrastructure projects but Nazi ideology and a past of war crimes committed in support of the invading German armies.

On the Snowy Mountains hydro-electric scheme, for example, an Auschwitz survivor recognised an SS officer who had served at the camp. At the Commonwealth Railways project in Port Augusta, Nazi cells were seen doing drills, giving “Heil Hitler” salutes and assaulting other migrants.

All these reports were angrily dismissed by Arthur Calwell, the ALP immigration minister, as “gross and wicked falsehoods”. His Liberal successor, Harold Holt, denigrated the Jewish community’s charges that Nazis were active in Australia as those of a minority sectional interest.

Both Labor and Liberal governments conducted a systematic cover-up of the import of Nazis to hide their connivance in assisting them into Australia to counter the left.

The Liberals were least shy about openly embracing their new anti-communist buddies. A Hungarian fascist was president of the Hungarian branch of the New Australian Liberal and Country Movement. Following the establishment by Nazi emigres in Australia in 1957 of the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations (ABN), a peak body of ultra-right migrant groups, senior Liberal politicians flocked to support it. Victorian Premier Henry Bolte and prime ministers John Gorton, Billy McMahon and Malcolm Fraser were just a few who shared platforms down the decades with their fascist hosts whom they extolled as noble anti-communist “freedom fighters”.

The first ABN president, a Hungarian mayor who organised and participated in the murder of his town’s 18,000 Jews, was a wanted war criminal, known to ASIO, who nevertheless became a prominent member of the Liberals’ Migrant Advisory Council.

In the 1970s, the Nazi emigres became entrenched in the NSW branch of the Liberal Party. Heading a powerful, extreme-right, pro-fascist faction (dubbed the “Uglies”) was Leo Urbancic, a senior Nazi propagandist in Slovenia during the war. Such propaganda created a climate that made the mass killing of Jews, communists and Allied soldiers acceptable.

In 1961, when Liberal federal attorney-general Garfield Barwick announced that the government had “closed the chapter” on war criminals in Australia, an amnesty was in effect granted to Nazi murderers. This was presented, with twisted Cold War logic, as a triumph of democracy over “Communism”, the government trumpeting the “right of asylum” as its excuse for rejecting the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries’ requests for the extradition of war criminals. It was one in the eye for the evil Reds. The Labor “opposition”, which did not want to be seen as “soft” on communism, remained silent on the amnesty.

It took 40 years before an Australian government formally recognised the fact that Nazi war criminals were in Australia. In 1986, Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke, under pressure created by Aarons’ exposure of Nazi war criminals in an ABC radio series, established the Special Investigations Unit to track down Nazis for prosecution in Australia under an amended War Crimes Act.

However, because of the evidence trail having grown cold, the age of key witnesses and accused, and a lack of bureaucratic support, only three of the 800 suspects who were investigated were brought to trial, none successfully (thanks to obstructionist judges and prosecution blunders). Hawke also prevented the SIU from investigating ASIO’s role in protecting and employing Nazi war criminals. Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating pulled the plug on the unit in 1992.

Australia remains the only Western country with a significant Nazi war criminal problem which has no legislation to allow the deportation of suspects for trial in their homelands. The Howard government did pass legislation to deal with war criminals who arrived in Australia after 1997 (50 years behind the times as usual).

Only the Kalejs case has disturbed the complacent political waters, embarrassing the government into rushing through an extradition treaty between Australia and Latvia.

For more than 50 years, the Australian capitalist establishment has opened its doors and closed its eyes to fugitive Nazi mass killers. Aarons’ book is a solid, impressively documented indictment of successive Labor and Liberal governments’, top public servants’ and the spy agencies’ complicity in harbouring Nazis and war criminals.

Today, as thousands of refugees fleeing tyrannies around the world languish in Australian detention centres, they may well be wondering why the red carpet was rolled out for right-wing murderers and what this shows about the true colours of Australia’s “democratic” government.

The British-American coup that ended Australian independence

Guardian, John Pilger, Thu 23 Oct 2014

In 1975 prime minister Gough Whitlam, who has died this week [Oct 2014], dared to try to assert his country’s autonomy. The CIA and MI6 made sure he paid the price.

Across the media and political establishment in Australia, a silence has descended on the memory of the great, reforming prime minister Gough Whitlam. His achievements are recognised, if grudgingly, his mistakes noted in false sorrow. But a critical reason for his extraordinary political demise will, they hope, be buried with him.

Australia briefly became an independent state during the Whitlam years, 1972-75. An American commentator wrote that no country had “reversed its posture in international affairs so totally without going through a domestic revolution”. Whitlam ended his nation’s colonial servility. He abolished royal patronage, moved Australia towards the Non-Aligned Movement, supported “zones of peace” and opposed nuclear weapons testing.

Although not regarded as on the left of the Labor party, Whitlam was a maverick social democrat of principle, pride and propriety. He believed that a foreign power should not control his country’s resources and dictate its economic and foreign policies. He proposed to “buy back the farm”. In drafting the first Aboriginal lands rights legislation, his government raised the ghost of the greatest land grab in human history, Britain’s colonisation of Australia, and the question of who owned the island-continent’s vast natural wealth.

……………………………………… Whitlam demanded to know if and why the CIA was running a spy base at Pine Gap near Alice Springs, a giant vacuum cleaner which, as Edward Snowden revealed recently, allows the US to spy on everyone. “Try to screw us or bounce us,” the prime minister warned the US ambassador, “[and Pine Gap] will become a matter of contention”

Victor Marchetti, the CIA officer who had helped set up Pine Gap, later told me, “This threat to close Pine Gap caused apoplexy in the White House … a kind of Chile [coup] was set in motion.”

Pine Gap’s top-secret messages were decoded by a CIA contractor, TRW. One of the decoders was Christopher Boyce, a young man troubled by the “deception and betrayal of an ally”. Boyce revealed that the CIA had infiltrated the Australian political and trade union elite and referred to the governor-general of Australia, Sir John Kerr, as “our man Kerr”.

Kerr was not only the Queen’s man, he had longstanding ties to Anglo-American intelligence. He was an enthusiastic member of the Australian Association for Cultural Freedom, described by Jonathan Kwitny of the Wall Street Journal in his book, The Crimes of Patriots, as “an elite, invitation-only group … exposed in Congress as being founded, funded and generally run by the CIA”. The CIA “paid for Kerr’s travel, built his prestige … Kerr continued to go to the CIA for money”.

When Whitlam was re-elected for a second term, in 1974, the White House sent Marshall Green to Canberra as ambassador. Green was an imperious, sinister figure who worked in the shadows of America’s “deep state”……………………………..

The Americans and British worked together. In 1975, Whitlam discovered that Britain’s MI6 was operating against his government. “The Brits were actually decoding secret messages coming into my foreign affairs office,” he said later. One of his ministers, Clyde Cameron, told me, “We knew MI6 was bugging cabinet meetings for the Americans.” In the 1980s, senior CIA officers revealed that the “Whitlam problem” had been discussed “with urgency” by the CIA’s director, William Colby, and the head of MI6, Sir Maurice Oldfield. A deputy director of the CIA said: “Kerr did what he was told to do.”

…………………………….. On 11 November – the day Whitlam was to inform parliament about the secret CIA presence in Australia – he was summoned by Kerr. Invoking archaic vice-regal “reserve powers”, Kerr sacked the democratically elected prime minister. The “Whitlam problem” was solved, and Australian politics never recovered, nor the nation its true independence.

John Pilger’s investigation into the coup against Whitlam is described in full in his book, A Secret Country (Vintage), and in his documentary film, Other People’s Wars, which can be viewed on http://www.johnpilger.com/

70 years since Operation Hurricane: the shameful history of British nuclear tests in Australia

Red Flag, by Nick Everett, Sunday, 16 October 2022

At 9.30am on 3 October 1952, a mushroom cloud billowed up above the Monte Bello Islands, 130 kilometres off the coast of Western Australia. The next day, the West Australian reported: “At first deep pink, it quickly changed to mauve in the centre, with pink towards the outside and brilliantly white turbulent edges. Within two minutes the cloud, which was still like a giant cauliflower, was 10,000 feet [three kilometres] high”.

Derek Hickman, a royal engineer who witnessed the blast aboard guard ship HMS Zeebrugge, told the Mirror: “We had no protective clothing … They ordered us to muster on deck and turn our backs. We put our hands over our eyes and they counted down over the tannoy [loudspeaker]. There was a sharp flash, and I could see the bones in my hands like an X-ray. Then the sound and the wind, and they told us to turn and face it. The bomb was in the hull of a 1,450-ton warship and all that was left of her were a few fist-sized pieces of metal that fell like rain, and the shape of the frigate scorched on the seabed.”

Operation Hurricane was, up until that moment, a closely guarded secret. ……………………….

Throughout 1946, negotiations took place between the British and Australian governments, culminating in an agreement to establish a 480-kilometre rocket range extending northwest from Mount Eba (later moved to Woomera) in outback South Australia.

On 22 November 1946, Defence Minister John Dedman informed parliament of cabinet’s decision to establish the rocket range. Peter Morton, author of Fire Across the Desert: Woomera and the Anglo-Australian Joint Project 1946–1980, explains that Dedman reiterated claims made in a report by British army officer John Fullerton Evetts that related to the original proposed site at the more remote location of Mount Eba, not Woomera. Dedman told parliament that Australia was the only suitable landmass in the Commonwealth for such testing, the designated area was largely uninhabited and that impacts on the Aboriginal population in the Central Aboriginal Reserves would be negligible. According to Morton, there were approximately 1800 Aboriginal people living on the reserves at the time. The Committee on Guided Projectiles would immediately begin consultations with the director of Native Affairs and other authorities, Dedman told parliament.

Dedman’s announcement ignited fierce opposition. In her book Different White People: Radical Activism for Aboriginal Rights 1946-1972, Deborah Wilson describes the independent Labor member for Bourke, Doris Blackburn, spearheading a peace movement strongly supported by the Australian Communist Party. She published her speeches in the CPA newspaper, Tribune. Blackburn was the widow of lawyer and parliamentarian Maurice Blackburn, whose left-wing views resulted in his expulsion from the ALP.

Blackburn insisted that the rocket range amounted to a grave injustice against a “voiceless minority”, Australia’s First Nations people. In March 1947, medical practitioner Charles Duguid told a 1300-strong Rocket Range Protest Committee meeting in Melbourne that he was appalled by the government’s blatant “disregard” for the rights of Aboriginal people. According to a Tribune report, he asked those present: “Shot and poisoned as they were in the early days, neglected and despised more lately, will most of our Aborigines [sic] now be finally sacrificed and hurried to extinction by sudden contact with the mad demands of twentieth century militarism?”

Dedman, supported by the Menzies-led opposition, dismissed concerns expressed by Duguid and anthropologist Donald Thompson that contact between military personnel and Aboriginal people living in the military zone would have devastating consequences for their traditional way of life. Deploying assimilation arguments, Dedman insisted that contact between military personnel and “natives” in the area would simply accelerate an inevitable process of detribalisation.

Meanwhile, Liberal and Country Party politicians railed against Duguid and other opponents of the project, labelling them dupes of communism with a lax attitude to the nation’s security, according to Wilson. They called on the Chifley government to follow the example of the Canadian royal commission established to weed out alleged communist spies in public sector employment…………….

In June 1947, federal parliament rushed through the Approved Defence Projects Protection Bill, a gag tool preventing critical commentary about the government’s defence policy. Transgressors were threatened with fines of up to £5,000 or a 12-month prison sentence.

Under the cover of “national security”, federal bans were imposed on union officials visiting the Woomera rocket range site, now a no-go area for anyone other than sanctioned military personnel. Anti-communist fearmongering helped set the scene for the Chifley government’s establishment of a new and powerful security organisation, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), in 1949.

In mid-1947, 446 kilometres north of Adelaide, the Woomera township was swiftly constructed on the traditional lands of the Kokatha people. By mid-1950, its population had grown to 3,500 and, over the following decade, doubled to 7,000. Roads gouged through Aboriginal country. Electricity and telegraph lines soon followed, connecting the military base with centres of political power.

The nature of the missile testing remained a top secret to all but those firmly ensconced within the upper echelons of the Department of Defence. However, rumours of a nuclear testing program abounded. The detonation of a 25-kiloton nuclear weapon off the Monte Bello Islands made Britain’s nuclear ambitions, and the Australian government’s complicity, visible for the world.

In the film Australian Atomic Confessions, witness May Torres, a Gooniyandi woman living at Jubilee Downs in the Kimberley, described observing a cloudy haze that remained in the sky for four or five days. At the time she did not know that it carried radioactive particles that were to contribute to cancer and an early death for many of her community, including her husband, in the early 1960s.

Another witness, Royal Australian Air Force pilot Barry Neale, described aircraft operating out of Townsville identifying nuclear particles in the air three days after the detonation. Two days later, New Zealand Air Force aircraft similarly observed radioactive particles that had emanated from Operation Hurricane. Still today, signs on the Monte Bello islands warn visitors about the dangers of elevated radiation levels.

In October 1953, two nuclear tests (Operation Totem) took place at Emu Field, 500 kilometres northwest of Woomera. In May and June 1956, nuclear testing returned to the Monte Bello Islands. Operation Mosaic detonated the largest ever nuclear device in Australia: a 60-kiloton weapon four times as powerful as that which had destroyed Hiroshima.

My aunt was among the children who witnessed the Monte Bello explosion from the jetty in the Pilbara town of Roebourne. The spectacle left her and her siblings covered in ash, oblivious to the toxicity of the fallout they were exposed to.

Meanwhile, west of Woomera, Aboriginal people were being relocated from their traditional lands. In preparation for Operation Buffalo, a series of four nuclear tests at the Maralinga Testing Ground, an 1,100 square kilometre area was excised from the Laverton-Warburton reserve and declared a no-go area.

Two patrol officers, William MacDougal and Robert (Bob) Macaulay, were given the nearly impossible task of keeping Aboriginal people out of the no-go area. The pair’s reports to the range superintendent were frequently censored, according to Morton.

In December 1956, a Western Australian parliamentary select committee, led by Liberal MLA William Grayden, visited the Laverton-Warburton Ranges. The select committee’s report (the Grayden Report) identified that displaced Aboriginal people suffered from malnutrition, blindness, unsanitary conditions, inadequate food and water sources, and brutal exploitation by pastoral interests.

News reports in the Murdoch-owned Adelaide News dismissed the committee’s findings, insisting that the claims could not be substantiated. Responding to the Murdoch media whitewash, Tribune reported on 9 January 1957 that the committee had “ripped aside the screen that has veiled the cruel plight to which our [g]overnments condemn Australian Aborigines”.

Tribune asserted that “huge areas of the most favourable land are being taken from [Aboriginal] reserves and provided for mining interests, atomic and guided missile grounds, and other purposes”.

A subsequent Tribune article reported a week later on the observations of Pastor Doug Nicholls, who accompanied the West Australian minister for native welfare, John Brady, on a tour of the Warburton-Laverton district. According to Tribune:

“Pastor Nicholls said that at Giles weather station, deep in the heart of the best hunting grounds in the Warburton reserve—a region that the Government had stolen as part of the Woomera range—the white people lived like kings, and the Aboriginal people worse than paupers … The Commonwealth had spent a fortune on Woomera, but has not even supplied a well for the Aboriginals.”

The Grayden Report deeply shocked the public. A film documentary produced by Grayden and Nicholls, Their Darkest Hour, further exposed these crimes. Wilson describes scenes from the film:

“Images of malnourished, sick and poverty-stricken Aboriginal people bombard the viewer. A mother’s arm has rotted off with yaws. A blind man with one leg hobbles grotesquely on an artificial leg stuffed with furs and bandaged into an elephant-like stump. Malnourished children with huge swollen bellies stare blankly at the camera. A baby lies deathlike beside a mother too weak to walk. A sickening close-up of a toddler who fell into a fire reveals cooked flesh covered with flies. Skeletal remains of a man, dead from thirst, lie beside a dried-up waterhole. As the film concludes, his body is buried in an unmarked grave.”