U.S. military has poisoned millions of acres in the mismanagement of weapons and their wastes

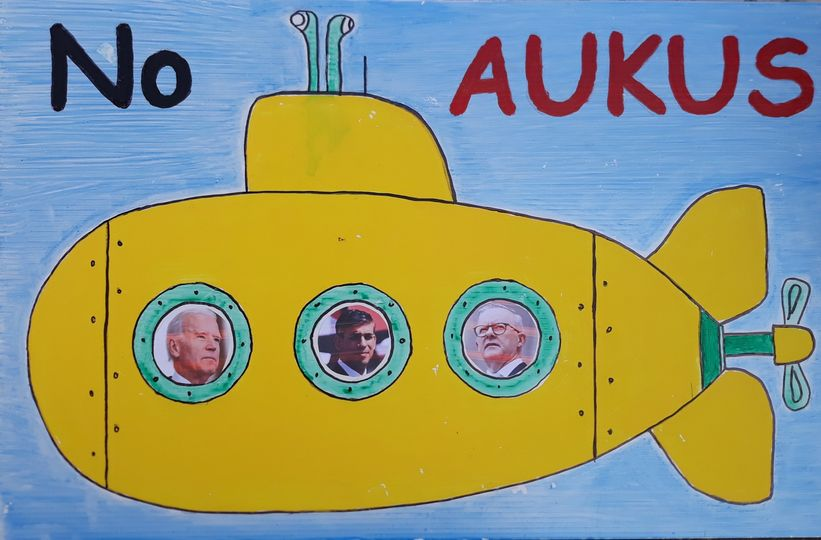

This article raises the question of what the authorities are doing in Woomera, South Australia with weapons wastes?

More than three decades ago, Congress banned American industries and localities from disposing of hazardous waste in these sorts of “open burns,’’ concluding that such uncontrolled processes created potentially unacceptable health and environmental hazards.

That exemption has remained in place ever since, even as other Western countries have figured out how to destroy aging armaments without toxic emissions.

Federal environmental regulators have warned for decades that the burns pose a threat to soldiers, contractors and the public stationed at, or living near, American bases.

“They are not subject to the kind of scrutiny and transparency and disclosure to the public as private sites are,”

How The Pentagon’s Handling Of Munitions And Their Waste Has Poisoned America

How The Pentagon’s Handling Of Munitions And Their Waste Has Poisoned America

Many nations have destroyed aging armaments without toxic emissions. The U.S., however, has poisoned millions of acres. Huffington Post, Co-published with ProPublica 20 July 17 RADFORD, Va. — Shortly after dawn most weekdays, a warning siren rips across the flat, swift water of the New River running alongside the Radford Army Ammunition Plant. Red lights warning away boaters and fishermen flash from the plant, the nation’s largest supplier of propellant for artillery and the source of explosives for almost every American bullet fired overseas.

Nearby, Belview Elementary School has been ranked by researchers as facing some the most dangerous air-quality hazards in the country. The rate of thyroid diseases in three of the surrounding counties is among the highest in the state, provoking town residents to worry that emissions from the Radford plant could be to blame. Government authorities have never studied whether Radford’s air pollution could be making people sick, but some of their hypothetical models estimate that the local population faces health risks exponentially greater than people in the rest of the region.

In the United States, outdoor burning and detonation is still the military’s leading method for dealing with munitions and the associated hazardous waste. It has remained so despite a U.S. Senate resolution a quarter of a century ago that ordered the Department of Defense to halt the practice “as soon as possible.” It has continued in the face of a growing consensus among Pentagon officials and scientists that similar burn pits at U.S. bases in Iraq and Afghanistan sickened soldiers.

Federal records identify nearly 200 sites that have been or are still being used to open-burn hazardous explosives across the country. Some blow up aging stockpile bombs in open fields. Others burn bullets, weapons parts and — in the case of Radford — raw explosives in bonfire-like piles. The facilities operate under special government permits that are supposed to keep the process safe, limiting the release of toxins to levels well below what the government thinks can make people sick. Yet officials at the Environmental Protection Agency, which governs the process under federal law, acknowledge that the permits provide scant protection.

Consider Radford’s permit, which expired nearly two years ago. Even before then, government records show, the plant repeatedly violated the terms of its open burn allowance and its other environmental permits. In a typical year, the plant can spew many thousands of pounds of heavy metals and carcinogens — legally — into the atmosphere. But Radford has, at times, sent even more pollution into the air than it is allowed. It has failed to report some of its pollution to federal agencies, as required. And it has misled the public about the chemicals it burns. Yet every day the plant is allowed to ignite as much as 8,000 pounds of hazardous debris.

“It smells like plastic burning, but it’s so much more intense,” said Darlene Nester, describing the acrid odor from the burns when it reaches her at home, about a mile and a half away. Her granddaughter is in second grade at Belview. “You think about all the kids.”

Internal EPA records obtained by ProPublica show that the Radford plant is one of at least 51 active sites across the country where the Department of Defense or its contractors are today burning or detonating munitions or raw explosives in the open air, often in close proximity to schools, homes and water supplies. The documents — EPA PowerPoint presentations made to senior agency staff — describe something of a runaway national program, based on “a dirty technology” with “virtually no emissions controls.” According to officials at the agency, the military’s open burn program not only results in extensive contamination, but “staggering” cleanup costs that can reach more than half a billion dollars at a single site.

The sites of open burns — including those operated by private contractors and the Department of Energy — have led to 54 separate federal Superfund declarations and have exposed the people who live near them to dangers that will persist for generations.

In Grand Island, Nebraska, groundwater plumes of explosive residues spread more than 20 miles away from the Cornhusker Army Ammunition Plant into underground drinking water supplies, forcing the city to extend replacement water to rural residents. And at the Redstone Arsenal, an Army experimental weapons test and burn site in Huntsville, Alabama, perchlorate in the soil is 7,000 times safe limits, and local officials have had to begin monitoring drinking water for fear of contamination.

Federal environmental regulators have warned for decades that the burns pose a threat to soldiers, contractors and the public stationed at, or living near, American bases. Local communities – from Merrimac, Wisconsin, to Romulus, New York – have protested them. Researchers are studying possible cancer clusters on Cape Cod that could be linked to munitions testing and open burns there, and where the groundwater aquifer that serves as the only natural source of drinking water for the half-million people who summer there has been contaminated with the military’s bomb-making ingredients……..

ProPublica reviewed the open burns and detonations program as part of an unprecedented examination of America’s handling of munitions at sites in the United States, from their manufacture and testing to their disposal. We collected tens of thousands of pages of documents, and interviewed more than 100 state and local officials, lawmakers, military historians, scientists, toxicologists and Pentagon staff. Much of the information gathered has never before been released to the public, leaving the full extent of military-related pollution a secret.

“They are not subject to the kind of scrutiny and transparency and disclosure to the public as private sites are,” said Mathy Stanislaus, who until January worked on Department of Defense site cleanup issues as the assistant administrator for land and emergency management at the EPA.

Our examination found that open burn sites are just one facet of a vast problem. From World War I until today, military technologies and armaments have been developed, tested, stored, decommissioned and disposed of on vast tracts of American soil. The array of scars and menaces produced across those decades is breathtaking: By the military’s own count, there are 39,400 known or suspected toxic sites on 5,500 current or former Pentagon properties. EPA staff estimate the sites cover 40 million acres — an area larger than the state of Florida — and the costs for cleaning them up will run to hundreds of billions of dollars.

The Department of Defense’s cleanups of the properties have sometimes been delegated to inept or corrupt private contractors, or delayed as the agency sought to blame the pollution at its bases on someone else. Even where the contamination and the responsibility for it are undisputed, the Pentagon has stubbornly fought the EPA over how much danger it presents to the public and what to do about it, letters and agency records show.

Chapter 1. Rules With Exceptions……..

Chapter 2. Debating the Dangers…….

Chapter 3. Awakening to Threats…….

Chapter 4. Risks and Choices……. alternatives only seem to be deployed after communities have mobilized to fight the burning with a vigor that has proven elusive in many military towns. “Sometimes it’s easier for everybody to just lie low and keep doing what they are doing,” Hayes added. “Short term thinking is the problem. In the immediate, it costs them nothing to keep burning.”

The success in Louisiana could be the start of a shift in momentum. In the 2017 Defense Department funding bill, Sen. Mitch McConnell, the majority leader, supported an amendment ordering the National Academy of Sciences to evaluate alternatives to open burning. ………

For Devawn Bledsoe, the foot dragging and decades of delay have led to profound disillusionment. For a long time, she thought her responsibility was to bring light to the issue. Now she thinks it takes more than that. “There’s something so immoral about this,” she said. “I really thought that when enough people in power — the Army, my Army — understood what was going on, they would step in and stop it.”

“It’s hard to see people who ought to know better look away.”

Nina Hedevang, Razi Syed and Alex Gonzalez, students in the NYU Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute graduate studies program, contributed reporting for this story. Other students in the program who also contributed were Clare Victoria Church, Lauren Gurley, Clare Victoria Church, Alessandra Freitas and Eli Kurland. http://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/entry/open-burns-ill-winds_us_5970112de4b0aa14ea770b08

No comments yet.

Leave a comment